Beau Welling is a busy man. For starters the Washington D.C. native, who was raised in South Carolina, runs his own design company. He works with Tiger Woods on other high-profile course projects. He has designed digital holes for the new TGL. Aside from golf, he’s the president of the World Curling Federation and has served on the board of the Carolina Ballet Theatre. There’s plenty more.

Welling has a physics degree from Brown and an international business degree from South Carolina, and he studied landscape architecture at the Rhode Island School of Design and Irish drama at Trinity College in Dublin. He started his working life for Siemens AG in Germany, then became a banker in Charlotte, North Carolina. Golf architect Tom Fazio hired Welling away to run the business side of Fazio’s design company, a 10-year stint during which Welling branched into course design itself. He launched Beau Welling Design in 2007 and almost immediately partnered with Tiger Woods on projects.

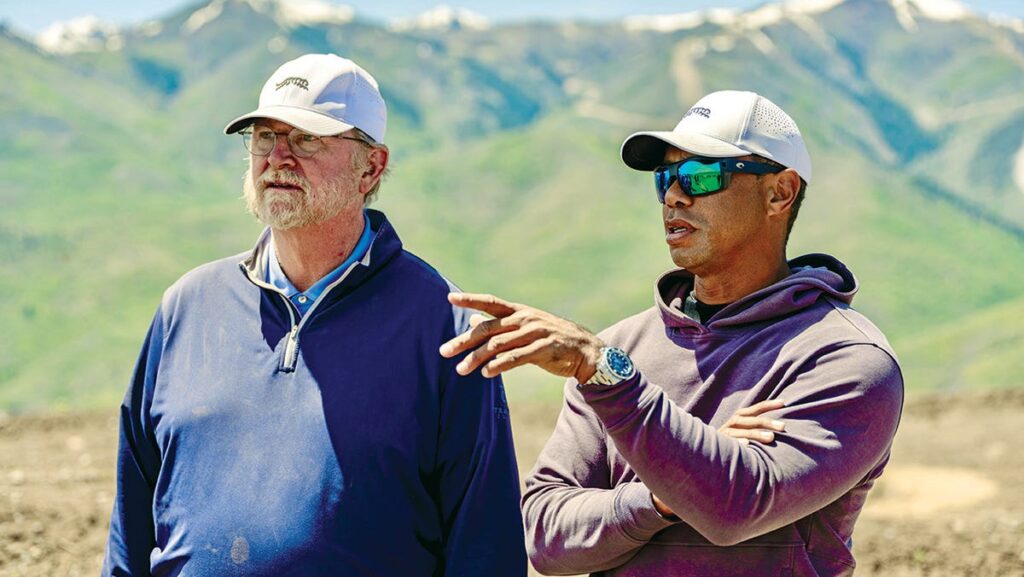

And Welling’s work goes well beyond just golf holes. He was hired by the PGA of America to not only lay out the Fields Ranch West Course at Omni PGA Frisco Resort in Texas, he master-planned the entire project that includes another course designed by Gil Hanse and Jim Wagner, a hotel, a par-3 course, a slew of restaurants and a Topgolf lounge, among other amenities. In his work with Woods, Welling has helped design courses such as Payne’s Valley at Big Cedar Lodge in Missouri and Bluejack National in Texas. The pair currently has three projects underway: Trout National in New Jersey for baseball star Mike Trout, Marcella Club in Utah and Bluejack Ranch in Texas.

So . . . not just some guy on a bulldozer. Welling said he loves data, and it’s clear he feels the same for the pursuit of new challenges and opportunities. Golfweek picked his brain on several topics in a recent sit-down in Orlando, covering everything from golf’s current boom to what it’s like to partner with Woods. The following excerpts are from that conversation.

Golfweek: How would you describe the industry and your work these days, having gone from a period of relatively slow business after the financial crash in 2008 and now to business booming since COVID?

Beau Welling: I’ve been doing this now for not quite 30 years of my life, and this is as exciting as it’s ever been. And sometimes my staff and my wife ask, “Are you too busy?” But I remember when the phone didn’t ring at all, and you get involved in this business to do stuff and build things. So it’s awesome to be busy. I love it.

What’s it like for you building a private club versus building a public course? How do you approach that as a design philosophy?

To me, the golf design is not that much different. We’re big-tent people, and we want everyone to have a good time. People use the word playability, and it means different things to different people. To us it means having an enjoyable round of golf regardless of skill level.

So a good player wants to be challenged or tested. A good player doesn’t want to go play some cake, easy golf course. But a not-so-good player wants to feel like they have a chance and it’s not impossible. It sounds like an oxymoron or something, but it’s our job as designers to do that whether it’s public or private. And then, how do you do it becomes a big question.

Every golf designer in the world says the same thing about playability, but then so many designers go and put sand everywhere. The reality is, a good player plays out of sand really, really well. And the not-so-good player can’t play out of sand at all. So in my mind, some designers are doing the opposite of what they say they’re going to do.

For us, width becomes really important. What happens around greens becomes very important. A good player approaches a green from a long distance, i.e. they hit greens in regulation. A not-so-good player approaches greens from a very short distance, i.e. they rarely hit greens in regulation. So you have to be mindful of what’s happening short of a green, because that really affects a not-so-good player versus a good player.

People say, you can’t do all that. To me, Augusta National is proof point No. 1. It challenges the best male and female players once a year. But my 81-year-old mother loves going to Augusta National. It has nothing to do with Bobby Jones or Alister MacKenzie or the Masters. It has to do with that she can hit her golf ball, go find it and hit it again. And when she gets up on those greens, she three- or four-putts, but in reality she probably three- or four-putts a flat green. So it’s great, super playable.

Where the public part comes in, is volume. Not across the board but generally, the volume of play at a private course will be less than the volume of play at a public course. So you have to start sizing things appropriately and be more mindful of that. So that might mean bigger greens, more pin-able areas on greens, bigger tees that you’re thinking about. Cart paths and access on and off, how that works because you don’t want turf to get worn out.

So much recent work in the industry has focused on private courses. Is it financially possible these days to build a regular daily-fee golf course? Not something huge at a high-end resort, just a daily-fee golf course.

I think that from a capital standpoint, it’s hard. It’s hard for for-profit capital, because whomever is providing the capital wants a return. That math is really, really hard.

So I think either you have to have some sort of benevolence – and there’s been plenty of examples of private-public partnerships building great public courses, like what Gil (Hanse) did with the PGA at The Park in West Palm, or like what Tom Doak did out in Houston at Memorial Park. I think you either have to have that, or you have to have some municipality say for whatever reason that they’re into golf and want to build something. Or it’s got to be set into a resort or some version of housing, so that the capital is repaid in some other way. I wish that wasn’t the way it is, but I think that’s just the reality of how it is.

So all these private South Carolina courses and Florida courses, that’s just private capital that doesn’t care. They just want to have great places. Will we ever see that at a public course? We might. Maybe one of these millionaire guys will say, “I want to build a great place.”

How important is it for you to have done a big public facility like PGA Frisco to show people your work?

It meant a lot to me. When it started, they went out to five architects with the brief, and you have to compete for the job. When I saw the brief, I was the equivalent of “The Bad News Bears,” and I had no chance to get hired. It was all these big guys and little old me.

But when I saw the brief, it reminded me of where I grew up, like instantaneously. So I grew up at Greenville Country Club (in South Carolina). It’s private and not public, but we had a par-3 golf course. That’s where I learned the game. And then us kids would get good enough to go to the big course, which was sort of an open, older, friendly kind of golf course. And when we kind of got good enough there, we could go to Chanticleer, another part of the club (that’s ranked by Golfweek’s Best as the No. 12 private course in the state). So it’s almost like this ladder.

I immediately saw what they were talking about for PGA Frisco, that it could be Greenville Country Club on steroids in terms of impact for the city of Frisco and even a greater impact with all these levels of golf in the same place. So I went crazy about it, like “We have to get involved in this project.”

And I did the craziest presentation ever. We were the fifth of the five to present. We walk in the room with the stakeholders, and you could tell they’re tired and have been listening to golf weirdos talk about golf design all day. . . . We did the assignment they asked for, but then we critiqued our performance of the assignment, saying why this is all wrong. In fact, the question was wrong. We said, “You need to be thinking about this instead,” and then the big reveal was they needed to be thinking about a resort hotel, which was not a part of the original brief. So they asked if we could do the West Course and be the planners for the whole thing, and we master-planned the entirety of the whole thing.

I’m very proud of it because to me – and of course I’m biased – the whole environment is a manifestation of a really good step for the game of golf in a direction that is more open, more accessible, more welcoming, more fun than our granddads’ golf resort. This is not our granddads’ golf resort, and there’s something that’s super cool about that.

Switching topics here: What can we learn from TGL, and what you did with the digital holes you designed for them, that applies to real on-the-ground golf holes?

Our involvement with TGL started pretty early through our Tiger connection. What’s now known as the Green Zone (which includes a putting surface that can be spun and adjusted in myriad ways, plus bunkers and a 40-yard approach circle), we were involved in helping conceptualize the vision and design all that. And that was complicated . . . super complicated.

But we had an incredible team of people. One of my memories from TGL will always be the team that they put together to pull this off with a lot of really, really smart people. They’re truly team-based, no big egos, just everyone looking for solutions and everybody with an area of expertise.

Then we were asked to design some of the virtual holes to marry up to the Green Zone. Other design firms were involved as well, and they actually did more holes than us, partly because we were still working on the Green Zone.

When they asked us to do some virtual holes, my first instinct was, let’s take advantage of the lack of constraints in the virtual world, but put them in real-world environments. I had it in my mind that they should have a sense of place. So when the New York team plays, we should have holes in Central Park and we should have holes down Wall Street. For the Atlanta team, we should have holes on the Chattahoochee River or through CNN Tower, whatever. That kind of proved to be a little bit challenging for Year 1 to model all that non-golf stuff. And so, (architect) Auggie Pizá in particular, he sort of went that direction more (with his TGL holes), what I call a video game hole.

At some point, I started to realize that we really need to take advantage of stuff we can do. One hole that they use a lot, Quick Draw they call it, plays around a canyon. It has a lot of options and a split fairway, and you can play to a section of fairway on a kind of plinth in the canyon. In the real world, we have to figure out, how do we get people out there and mowers and all that kind of stuff? But in the virtual world, we don’t have to worry about that kind of stuff.

To answer your question, though, about what has been helpful in the translation back to the real world: There’s been some modeling stuff that we’ve been able to do. A simple example would be, if we’re working at Jonathan’s Landing and we shape in a bunker, then we look and decide that maybe it should be 10 yards over that other way. So you flag it out and the guy on the bulldozer starts to operate, and we come back the next day to look at it. But in this virtual world, that’s two or three key strokes to move that bunker and see what it looks like.

You mentioned Tiger with the TGL starting. You’ve had a relationship that goes back more than 15 years. What is that relationship like now for you as you work on the new courses like Trout National, Bluejack Ranch and Marcella Club?

You know, it’s a great working relationship. It always has been. I think that I view him as a client. I work for him. He’s got things that he believes, and my role is to help him accomplish what he’s trying to do. Luckily, we view golf through a very similar lens. He’s so smart and so creative, and he’s almost like a computer when he thinks about a golf shot, calculating all these risk/reward sort of things and different ways to hit shots and trajectories and all this kind of stuff. And so I find that very, very fascinating.

He loves links golf. My mother’s half Irish, so I’ve lived in Ireland (in Dublin) and played lots and lots of links golf, and it’s a big influence on me. So I think we sort of are connected that way. The way Tiger speaks about it is, let the ground be the friend to the golfer, the ability to play shots on the ground opposed to just in the air. That’s very much a links thing.

Very early on, he was like, “I think I know how to build a hard golf course, but I don’t want to do that. How do I build a golf course that everybody’s going to enjoy?” Which I thought, for a person starting out in this business, was really astute.

So it’s a great working relationship, and I’m just trying to help him accomplish his goals and objectives. He’s got three projects in construction right now, and that’s the most ever, so it’s really awesome to see that his attention is getting into this realm more and more. And he’s got some really awesome projects.

– This article originally appeared in the March print issue of Golfweek magazine.

Read the full article here