As college football races toward the start of the revenue-sharing era on July 1, a new battle is unfolding — not on the field, but in the fine print. Schools and player agents are clashing behind the scenes over the language of contracts, with some universities pushing aggressive terms that raise eyebrows across the industry.

While some players received front-loaded payments ahead of July 1, many are now encountering multi-page agreements drafted by school lawyers, packed with provisions that attempt to lock in control, minimize financial risk, and, in some cases, limit players’ rights.

“Since this is new and uncharted territory, they’re trying to put in as many things as they can think of and protect that university and see what they get push back on and what they don’t,” Mit Winter, an attorney who works heavily in the NIL space told CBS Sports.

Put another way by an NIL agent: “They’re throwing everything they can and the kitchen sink.”

That sink?

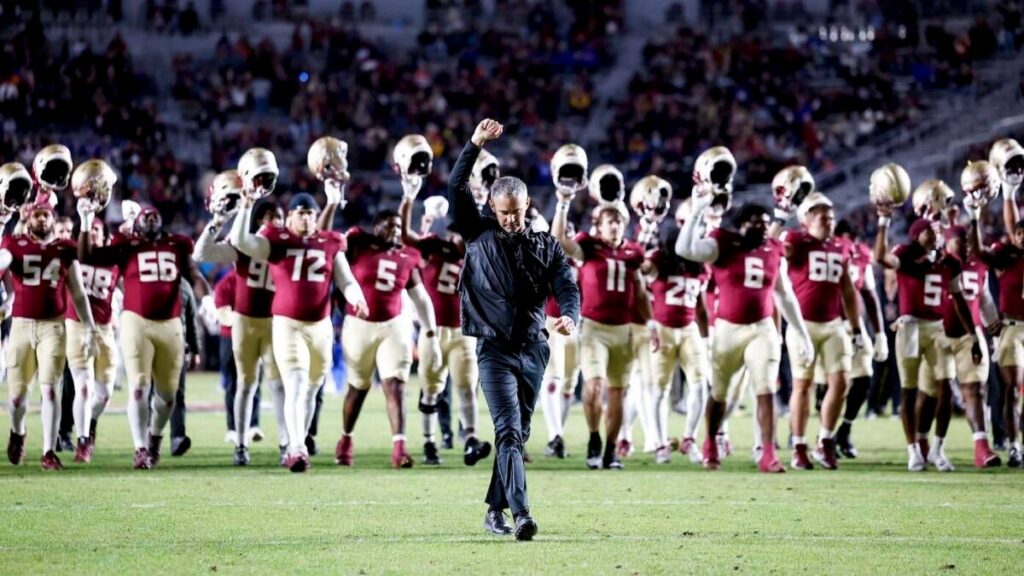

It’s appearing quite often in Tallahassee, according to multiple agent sources who have at least one player on the Florida State roster.

The Seminoles have included what those agents describe as aggressive language in their rev share contracts, which cover a broad range of issues and are issued directly by the school.

One clause, which CBS Sports has seen a copy of, allows the team to extend a player at the end of their contract unilaterally without having to negotiate with the player. Another section on team rules — common in most NIL or rev share deals — includes a maximum $2,500 fine on the first offense if a player loses team equipment such as a pair of cleats. The max fine for using a controlled substance for the first time is $1,000.

There’s another clause about things that would constitute a breach of contract. Among them is “illness or injury which is serious enough to affect the value of rights granted to the school.” The way it’s written allows Florida State to renegotiate or even cancel a player’s contract at its discretion after any sort of injury — among other potential liquidated damages provisions included as part of the contract — including those that happen on the football field.

There’s also a provision that, depending on how it’s interpreted, could limit an athlete’s right to counsel during any future negotiations.

“Some of the concepts are pretty standard,” an agent who represents at least one Florida State player said; they were granted anonymity to allow them to speak freely. “But FSU is going about this far more aggressively than any school I’ve seen. I’m disappointed by the adversarial nature of these contracts.”

It’s not just agents who take exception with the way FSU is attempting to write its rev share contracts. CBS Sports contacted at least one general manager from every Power Four conference to understand if some of Florida State’s provisions are considered normal.

Said one Big Ten general manager of the three stipulations above: “That’s not normal.”

Said a GM from the Big 12: “I do understand they have all the leverage, but f***.”

Still, other agents contacted by CBS Sports said while Florida State is contentious with its reworked rev share agreements, the pushy and controlling language isn’t exactly uncommon.

“I don’t think Florida State is the worst at all in this business,” said an agent with a player on FSU’s roster. “There are schools I trust less.”

Florida State, when reached for comment, offered this statement via a spokesperson in response to questions about some of the provisions CBS Sports highlights in this piece.

“As we enter into a new age of collegiate athletics, Florida State has put together an agreement that provides deliverables and expectations for all parties. Each individual situation will be unique and the hypotheticals are impossible to predict. However, we are committed to continuing to provide an elite experience for our student-athletes in all aspects of their collegiate career. Florida State is looking forward to the mutually beneficial partnerships with our student-athletes in this new era.”

All of this comes at an unstable time in college athletics where schools are attempting to balance what is essentially a pay-for-play model wrapped in the guise of a payment system still built around a school’s access to a player’s name, image and likeness.

That push and pull is something Sports and Higher Education Attorney James Nussbaum, of Church, Church Hittle + Antrim, which consults and works with double-digit D-I programs, said is creating unsteady language in which negotiating agents want things similar to employee protections while schools want as much flexibility as possible if a player’s NIL value tanks due to something like an injury.

“Everybody knows that you have to participate in athletics for your name, image and likeness to be worth anything to the schools you’re going to,” Nussbaum said. “At the same time, we’re trying to continue under this framework where we’re saying this isn’t pay for play.

“Part of why I think it’s difficult to negotiate is because of the framework where we’re not able to compensate you directly for your participation. … There’s a lot of grey area between those two poles.”

Not every Florida State player has been delivered their revenue sharing contract at this point. CBS Sports contacted the agents of several of the top transfer additions for Florida State this offseason — shoe-in starters and borderline top 10 players on the roster — and their money was mostly front-loaded ahead of July 1. They’re expected to see their rev sharing contracts in the coming days.

But a lot of players will have their payout split between the collective dollars and rev share. Some programs allow the terms of their collective contracts to carry over to their rev share deals. Florida State, however, had some players sign a memorandum of understanding, a one-page document that lays out the intended terms between two parties. Others were merely assured their collective deals would carry over into the rev share.

Florida State, like many other programs nationally, was only able to send out the full version of its rev share agreements once the House Settlement was approved on June 6.

In conversations with three agents who represent at least one Florida State player who has been sent their full rev share contract in recent weeks, the Seminoles seem to have settled on a standard contract for its roster. Big Ten and SEC schools generally work off a standardized contract the conference provides to its school. The ACC does not have a contract baseline for its programs.

That lack of universal standard in the ACC has led to some unique language from the Seminoles.

The option to extend

“[school] shall have, until the end of Student-Athlete’s NCAA eligibility, dependent, successive options to extend the Term under the same terms and conditions as the existing Term, unless the Parties mutually agree in writing to a change in such terms and conditions, for additional periods of one year by providing written notice of such extension (e-mail is sufficient) to Student- Athlete no later than twenty (20) days prior to the expiration of the then-current Term of the Agreement. Under such an extension option, the Total Compensation payable to Student-Athlete for the one-year extension period shall be a pro rata, annualized portion of the compensation set for the initial term.

That language, which allows Florida State to extend a student-athlete’s deal pretty much at will by the end of their contract, is considered uncommon when talking with agent and general manger sources across the country.

“That locks a kid in for the rest of his eligibility with no ability to negotiate,” said the agent who shared the contract draft language.

Many schools provide players a window to negotiate after every regular season. Other programs, like in the SEC, have begun writing in a “first right of refusal” clause, which allows them to match a higher offer if they receive one from another school.

But sources CBS Sports spoke to consider Florida State’s extension clause unusually one-sided.

“I’ve never seen that before,” Winter said. “I would say that’s not a usual provision.”

A lot of Florida State players will have multi-year deals as part of the wave of initial revenue sharing contracts, so that language won’t always apply. But it is language that would come up for those on one-year deals or in the future if an athlete reaches the end of their agreed contract length.

A FSU source said players are also able to ask for a renegotiation of terms at the end of a contract if both sides desire an extension. That source indicated the school’s intent is to negotiate in good faith.

Injury and breach of contract

“In addition to a breach of any specific provision of this Agreement, the following circumstances create a breach of contract by Student-Athlete:

1. Illness or Injury Impacting Value of NIL Rights. Student-Athlete experiences any illness or injury which is serious enough to affect the value of the rights granted to [school] under this Agreement; provided, however, that nothing herein shall affect or limit [school]’s obligations to provide Student-Athletes with medical coverage of injuries sustained as a result of participation in [school] Athletics as required by Section 16.4 of the NCAA Division I Bylaws, where applicable.”

A few schools CBS Sports spoke with for this story have language or have considered adding language that allows them to cancel or alter a player’s dollar amount if they suffer an off-field injury doing an unsanctioned activity. Florida State features that language within its rev share contract drafts that it’s sent to players and their representation.

But nobody CBS spoke with considered the way Florida State wrote the above injury provision as normal if the injury occurred in a football context.

“That’s excessive,” said an ACC Director of Player Personnel.

It’s different from the NFL where athletes are employees and there are injury protections for players if they were hurt in organized activities and a stated process for medical second opinions and injury settlements.

And while an agent CBS spoke with expects Florida State to ultimately remove that stipulation from the contract, the way it’s currently written gives FSU full control to adjust a player’s salary when any injury occurs.

“It’s the first time I’ve ever seen something like that with an injury,” another agent said. “The way they’re going about it, they’re having it all in writing where at their discretion they can renegotiate at any time. Guys get injured all the time. The terms are very friendly to them.”

There’s no telling how, or would, Florida State actually enforce the injury provision for breach of contract as written. But those who have seen the contract in the agent space worried that Florida State felt the need to include it in the first place to have that leverage over its athletes.

Team rules

It is common for teams to put program rules in contracts. A SEC GM CBS spoke with said they have a fine system, usually related to things like failed drug tests or weight violations.

A pair of Syracuse freshmen, offensive tackle Byron Washington and defensive back Demetres Samuel Jr., recently revealed on the “State of Orange” podcast the fine structure the Orange use for team violations.

“We get fines for missing more than two absences in class,” Samuel said. “We got class checkers. If you don’t have your jug or your tablet for like …”

Chimed in Washington:”That’s $50.”

Samuel said later in the interview that if players don’t meet weight for a third time in a week it can cost them a quarter of their monthly check.

Florida State has multiple pages of team rules included in their revenue sharing contract. They range from small — a maximum $100 on the first offense for things like tardiness to team events ($50 for academic activities) — to large with a maximum $2,500 reduction in compensation if a player loses any team gear or technology.

The substance abuse fines — be it steroids, marijuana or another substance — scale quickly. The first offense is a maximum of $1,000 reduction from total compensation. The second offense is a maximum 10% of the compensation. A third offense? It’s 50% and a possible dismissal at the head coach’s discretion.

“They’re a bit arbitrary,” an agent said. “One thing I pushed FSU athletics on is this language needs to tie to a policy, right? I have a player in the NFL and his contract has things like showing up to meetings, drug testing but it’s a rigid codified process. The way (FSU’s) policies are written in the contract they could effectively line up three cups, have a kid pee, say it’s a failure and come back in 20 minutes, do it two more times, call it three failures and that penalty for that is his contract value. … And there’s no appeals process.”

That agent also emphasized there’s no functional appeals process for an athlete or burden of proof the team must reach. They said the only recourse an athlete has to challenge a fine is arbitration, where the athlete will likely go up against a school’s general counsel office with infinitely more resources.

A push and pull between schools and agents

Winter had previously come across Florida State’s rev share agreement before talking with CBS Sports. His thought after reading it: “Jesus Christ, this one goes far.”

It’s not uncommon for schools to push the boundaries of what’s considered normal with contracts. Often schools will put many stipulations in deals they’re willing to take out if an agent raises a concern. That has already happened with a few provisions at Florida State, per sources, but many of the above tension points remain and others are set to arise as more of these contracts are sent out.

As for what gets taken out, it can often depend on the leverage a particular athlete has or the importance of the individual clause to the school.

To Nussbaum, this is a period of uncertainty given that schools don’t exactly know how enforcement will play out under the new NIL GO landscape, where schools are attempting to create maximum flexibility. He said it’s up to the school to set priorities for what they deem important within the contracts.

“This is where you really have to have some of these hard conversations with your board and president and say, ‘What are our goals here?'” Nussbaum said. “If it’s simply coming up with the most money we can to compensate these student athletes. That’s one approach. But I don’t think any school is taking that approach.

“Yeah, you’re coming up with something that has some precedential value that’s necessary in a competitive industry like this … I think schools are aware and don’t want to tie themselves down unnecessarily in the future but at the same time want to be competitive and recruit in a way that will set them up for the future.”

And it’s not as if aggressive or controversial language is limited to the rev share era.

CBS spoke to one agent earlier this summer who said one of his clients at another school initially received a contract that allowed a school to terminate for any “alleged” criminal activity with no stipulations for due process. Another school attempted to put in language for damages that if a player left the program before the end of his contract term, he’d need to pay back all money included in the contract, including “unearned money.”

“That’s problematic,” the agent said. “You haven’t made it yet. We understand there’s damages, but a lot of these contracts were back-loaded for when revenue share kicked in.”

Schools are trying to protect themselves from players consistently transferring following a cycle in which more than 4,000 FBS players entered the portal. That’s where aggressive liquidated damages and new buyout language included in many rev share comes from.

But in a sport without an employee-employer relationship or collective bargaining, schools and players are left on an island to negotiate deals, which is where the barrage of restrictive language comes from on the school’s side.

One of the agents CBS spoke to for this story would push back on the idea that’s all Florida State is doing.

While the contested language may end up being removed from the contract its presence, they said, it seems to go beyond a mere negotiating tactic.

“If that were truly their intent, they would write it like that and it’s only useful in cases of emergency,” the agent said. “For example, if they’re only trying to go for a catastrophic injury or when a kid can’t play for the rest of the season, why does the injury clause account for any injury that has an impact on NIL value? They had smart attorneys write these things. They would have written it that way. If you want it for only break glass in case of emergency, you have to put the glass in front of the letter.”

Read the full article here