If there was one criticism to be had Cardiff, the location of it’s statues would be a valid one.

Were you aware of a statue of Mahatma Gandhi hiding in the trees just a stones throw away from the Millennium Centre in Cardiff Bay? Gareth Edwards lurks outside a Primark store in the indoor Sr David’s shopping centre.

Therefore it is no surprise that you might have wandered past the Radisson Hotel in the middle of Cardiff, without noticing one of the nation’s sporting giants standing proudly on a plinth by the main road.

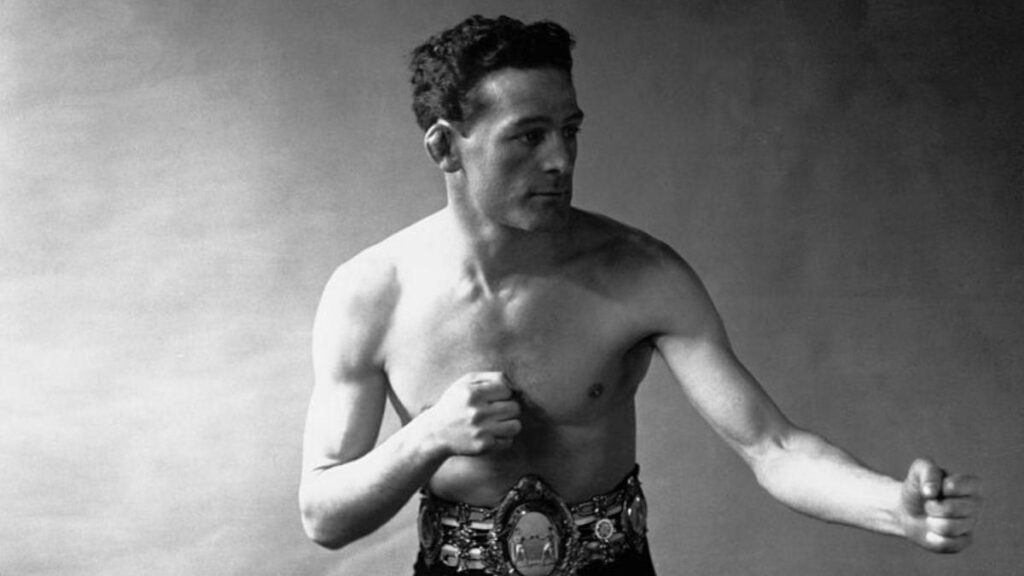

It’s impossible to compare Jim Driscoll with any other boxer or athlete in Welsh sporting history, and that’s to be expected when you consider his nickname.

Folk Hero

Peerless Jim Driscoll was born in the Adamsdown area of Cardiff in 1880.

When he passed away 44 years later, 100,000 people came on to the streets to pay respects to him.

Often, when sportsmen reach the upper echelons of notoriety, it is due to their contribution away from their field.

Consider Muhammad Ali, or even South Africa’s rugby union captain Siya Kolisi, two greats who are recognised for their actions and social sacrifices alongside their sporting successes.

Within the context of Driscoll, this personal sacrifice was responsible for the respect directed his way.

He gave up the chance to reach the peak of his sport because he promised to support his community.

The son of an Irish immigrant, Driscoll had a tough upbringing in desperate poverty at the end of the 19th century.

His father died after being hit by a train when Jim was only one.

His mother had to depend on the support of the church to help with raising her children, as well as maintaining her tough labouring job of loading potatoes and fish from the boats at the docks in Cardiff Bay.

Gaining Experience

Driscoll developed his artform in boxing booths.

Driscoll, like other legendary Welsh boxers Jimmy Wilde and Tommy Farr, would travel Britain’s fairs and carnivals challenging any one of the public who would be foolish enough to pay for the misfortune of stepping in the ring with him.

This meant battling with every size and shape, and doing so for hours.

The old legend goes that Driscoll would often stand on a handkerchief with his hands tied behind his back, challenging opponents to hit him on the nose.

It is estimated that Driscoll racked up over 600 unofficial fights in these boxing booths, and by 1901 he was ready to take the step forward into the professional ladder.

He went on for seven years in England and Wales before turning his sights towards the United States of America.

With his slick style and his ability to avoid punches by dancing around the ring, many people prophesised that the Welshman would be the next featherweight champion of the World.

In 1910 he finally got his chance, facing the champion Abe Attell.

Big Decisions

Most fights of the time followed the ‘no-decision’ rule, which meant that Driscoll would have to knock his opponent out to take the title away from him.

Atell insisted that this rule be put in place ahead of his fight against the Peerless.

Driscoll controlled the fight, but after 10 rounds he couldn’t finish off the American.

The fight had to have an official winner to please those that had bet on the fight, and the decision was unanimous.

Driscoll was the winner, but due to the no-decision rules the belt wouldn’t be his.

Driscoll had the opportunity of a rematch, but he refused.

He’d promised to perform at a show in Cardiff to raise money for Nazareth House orphanage.

He refused his chance to win a world title, ‘I never break a promise’ he declared.

Driscoll returned to Cardiff a hero for his unselfish actions. To many Driscoll was the unofficial World Champion.

Driscoll would fight again in the States, but following a period of illness, he was far off his best.

With the arrival of the First World War, and a series of other challenges his opportunity to become World Champion disappeared.

He is considered by many as the best British Boxer to never win a world title.

‘Peerless’

Jim Driscoll died of Tuberculosis at the age of 44 years on 30 January 1925.

As his coffin slowly made its way towards Cathays cemetery, thousands were on the streets of the capital, which at the time was home to only 200,000 residents.

If you were to visit the cemetery today – 100 years after his death – you would notice there are always flowers at his grave.

Which brings us back to the present.

Next time you’re shopping in Cardiff – and in particular the John Lewis department store – take the opportunity to leave through the back door.

Take care crossing four lanes of traffic, and there you will see, standing proud, a man with whom nobody compares.

Peerless.

Read the full article here