The most unusual path to the NBA wasn’t taken by some overlooked recruit or undrafted rookie.

Gregory Peim went from testing theories about the laws of the universe at the world’s largest particle accelerator to unlocking the secrets of pick-and-roll defense and player evaluation for the Los Angeles Clippers.

Advertisement

Northeastern University theoretical physicist Pran Nath remembers Peim knocking on his office door 16 years ago as a soft-spoken graduate student. Peim wanted Nath to be his advisor while he pursued a doctoral degree in physics.

Over the next three years, Peim blossomed into, as Nath puts it, his “star student,” a relentless worker whose projects became his passion. The best of Nath’s protégés typically publish four-plus papers in prestigious physics journals. Peim published 13, studying the particle showers created by smashing atoms together at high speeds to glean new insights about dark matter, supergravity and other mysteries of our universe.

Peim’s body of work helped him secure a flood of offers for postdoctoral research positions. Prestigious institutes from as far as Geneva and Madrid reached out to Nath to beg him to persuade Peim to accept their offers, which, according to Nath, is “extremely rare.”

Had Peim seized the chance to go into research and academia like so many of his theoretical physics peers, Nath is certain “he’d have been very successful.” Peim instead made the unconventional decision to apply his expertise in data analysis to basketball, a detour that set him on a path to spending the past 11 years working for the Clippers, most of that as the team’s director of research and analytics.

Advertisement

The Clippers’ investment in Peim reflects the modern NBA’s obsession with mining new sources of data to gain even the slightest competitive advantage. NBA teams have cast a wide net in search of tech savants who can use AI tools to extract fresh insights, from optimal in-game defensive strategies, to the most effective lineup combinations, to which potential draft or free agency targets are being undervalued.

Analytics departments across the NBA are littered with former Wall Street financial analysts, strategic consultants to Fortune 500 firms and Google and Microsoft software engineers. The Toronto Raptors even snatched up an aerospace engineer who specialized in computational fluid dynamics after he sold them on the parallels between analyzing particle tracking data and player movement data.

As basketball analytics have altered front-office strategies, coaching methodologies and player development, NBA teams have become more and more secretive about how they use the heaps of data available to them. Yahoo Sports reached out to a half dozen teams asking them to make analytics staffers available in advance of this week’s NBA Draft. They all either didn’t respond or declined, citing concerns about divulging too many details and giving away their competitive advantage.

“Teams are very secretive,” said sports analytics pioneer Ben Alamar, who worked for seven years with the Cleveland Cavaliers and Oklahoma City Thunder.

Advertisement

When NBA teams first started dabbling with analytics, Alamar remembers many trying to hide their interest from their competitors by requiring new hires not to reveal who they were working for. Even now, according to Alamar, analysts “seldom talk about the kinds of modeling they are doing in any detail.”

“The transformation of the data into information is highly proprietary, as is the manner in which the teams use the data-driven information,”Alamar told Yahoo Sports. “They are always trying to protect the competitive advantage that they get from their analytics.”

(Dillon Minshall/Yahoo Sports illustration)

Russell Westbrook or Brook Lopez?

The analytics revolution that has transformed the NBA began in the early 2000s in an obscure corner of the Internet. Dean Oliver and other pioneers of the movement bounced ideas about pace, possessions and efficiency off each other on the APBRmetrics message board.

Advertisement

Whereas Major League Baseball front offices were already populated with Ivy League-educated statheads by then, the NBA hadn’t yet embraced the idea that Moneyball philosophies could translate to a 5-on-5 sport without distinct pitcher-versus-batter matchups. Possession-based NBA stats were years away from going mainstream. So was the crusade against inefficient post-ups and midrange shots.

Mike Zarren stepped into that world in 2003 when the Boston Celtics made him the NBA’s most overqualified unpaid intern. General manager Danny Ainge tasked the Harvard law student, quiz-bowl champion and statistics whiz with exploring how the Celtics could better incorporate data and statistical analysis into their player evaluation and in-game decision making.

Obtaining reliable data was a big early obstacle, Zarren said last year while participating in a panel discussion at the MIT Sloan Sports Analytics Conference. Zarren described typing 1,200 pages of NCAA box-score data into a spreadsheet while building an early draft model. He also recalled the ordeal of requesting NBA substitution data from a contact at the league office.

“Nobody had ever asked for that before,” said Zarren, now the vice president of basketball operations for the Celtics. “[The files] were stored somewhere after games, but nobody knew where they were.”

Advertisement

By the mid-2000s, NBA play-by-play data became more widely available, allowing for more evaluation of which lineups performed well together and which individual players impacted winning more than their box-score stats suggested. The scouting service Synergy also chopped up and tagged video clips of post-ups, pick-and-rolls, providing analysts a new data source to evaluate tactics and aspects of player value.

It wasn’t long before the most forward-thinking NBA teams recognized the opportunity investing in analytics offered.

A few respected members of the APBRmetrics community abruptly stopped posting as NBA teams created full-time positions for them or hired them as consultants. Among those was Alamar, then a Menlo College professor with a PhD in economics, a talent for statistical analysis and a passion for basketball.

In 2008, the Seattle SuperSonics were debating whether to take Russell Westbrook or Brook Lopez with the fourth pick in the NBA Draft. General manager Sam Presti hired Alamar as a consultant to help answer what he considered to be the fundamental question: Could Westbrook play point guard?

Advertisement

Over several exhausting but exhilarating weeks, Alamar and intern Jesse Gould pulled up video of every shot the 2007-08 UCLA Bruins attempted. They charted the distance of each shot, whether a pass set it up, who threw the pass and whether the shot went in.

The goal, Alamar told Yahoo Sports, was to assess “does Russ make the right decisions when he’s passing the ball?” What was the likelihood that a player made a shot when Westbrook passed him the ball? And how did that compare to Westbrook’s teammate and future NBA point guard Darren Collison? Or to other elite point guards in the 2008 draft?

The results of Alamar’s study supported Presti’s intuition that Westbrook could successfully be a primarily ball handler in the NBA after mostly playing off ball at UCLA. Westbrook scored better than Collison, according to Alamar. He also outperformed other elite point guards in the 2008 NBA Draft, with the exception of Derrick Rose.

At a pre-draft meeting with Presti and his full basketball staff, Alamar nervously presented his findings as straightforwardly and non-technically as he could. A month later, Seattle selected Westbrook over Lopez, the correct decision most would argue now.

Advertisement

“The evidence was not a slam dunk,” Alamar said. “But it was a piece of data in support of the decision that Sam ended up making.”

While many influential figures across the NBA recognized that embracing analytics meant delivering better information to decision makers, others were more cautious or closed-minded. Analytics pioneers often sought to gain the trust of skeptics in their organization by using data to confirm a concept that person already believed.

Roland Beech got off to a rocky start in 2009 when he went from consulting from home for the Dallas Mavericks to becoming the NBA’s first “stats coach.” Tech billionaire and analytics aficionado Mark Cuban believed that Beech could only make a difference if the statistician sat behind the bench during games, attended practices and meetings and got to better understand the problems head coach Rick Carlisle needed to solve.

On the first day of training camp, Carlisle understandably didn’t know what to do with a coach who had more experience running linear regressions than basketball drills. Carlisle only called on Beech to help when he split the team into groups of three and told players that the trio that made the fewest shots would have to run as punishment.

Advertisement

As luck would have it, the threesome whose baskets Beech was assigned to count included the Mavericks’ two biggest stars, Dirk Nowitzki and Jason Terry. They both snarled at Beech that his count was off after an equipment manager briefly distracted him and he turned his back for two or three shots.

“The rest of the way they keep yelling at me, but I don’t change my number,” Beech told Yahoo Sports. “Then at the end we lose by one. They are just incensed.”

Each time Nowitzki zoomed past while running his up-and-backs, Beech recalls him growling, “We have a f— stats guy who can’t count.”

“That was my introduction to the NBA,” Beech chuckled. “You would think I would have had the common sense to go with what the superstar said on this one.”

Advertisement

Over Beech’s six-year tenure with the Mavericks, the debate over the usefulness of basketball analytics slowly faded away. The math nerds had won. The 3-point revolution was underway. Midrange jumpers were vanishing from postgame shot charts. Concepts like scoring efficiency and rebounding percentage were seeping into the mainstream vernacular.

Beech gradually gained Nowitzki’s trust by helping Dallas identify its best lineup combinations, and find ways to exploit opponents’ weaknesses. The Mavericks captured Nowitzki’s lone NBA title in 2011 with a statistician behind the bench.

Recalled Beech proudly, “The biggest compliment Rick Carlisle ever gave me, he said, ‘I don’t think of you as a stats guy anymore. I think of you as a basketball guy who knows stats.’

“That’s when I knew I had made it.”

(Joseph Raines/Yahoo Sports illustration)

How to make data useful

The most important innovation of basketball’s analytics era was the brainchild of two Israeli entrepreneurs with a background in military surveillance.

Advertisement

Gal Oz and Miky Tamir created a camera-tracking system known as SportVU that played an important role in shaping the modern NBA.

The SportVU system used six high-resolution cameras perched in the catwalks of NBA arenas to collect precise player and ball movement data at 25 frames per second. A laptop connected to the cameras then beamed back millions of lines of geometric coordinates to video rooms across the NBA.

The technology had already been used in international soccer and cricket before STATS LLC acquired SportVU in December 2008. STATS then repurposed the system for basketball and found some eager NBA teams willing to pay to have it installed in their home arenas, first Dallas before the 2009-10 season, then Boston, San Antonio, Houston, Oklahoma City and Golden State a year later.

The early adopters recognized the potential value player tracking technology offered, but they struggled to figure out how to extract a competitive edge from endless raw data. The reports that STATS fed to NBA teams included stuff like the distance a player ran during a game, the top speed he reached or the number of times he touched the ball, decent video board trivia fodder but nothing useful to a coach.

Advertisement

“If you were somebody who didn’t know a ton about basketball and were told to provide some stats, that’s essentially what they produced,” Alamar said.

While NBA teams brainstormed better uses for the player-tracking data, their one- or two-man analytics staffs often lacked the tools, training or most importantly time to perform such daunting tasks. Beech also recalls the system starting out “buggy and unreliable” when the Mavericks first dabbled with it.

“The joke used to be,” Beech said, “that if there was a bald guy in the front row, sometimes the system would mistake his head for the ball.”

The tech startup that helped NBA teams find value in the player-tracking data possessed a rare blend of engineering chops and basketball acumen. Second Spectrum was loaded with former men’s and women’s basketball players from places like MIT or Caltech. Much of its staff participated in weekly pickup games down the street from its Los Angeles office.

[Analytics] not the end-all, be-all, but it’s part of the pie and it’s become more prevalent in recent years. Every team’s different in terms of how much weight they put in it.

Advertisement

“That was always the secret sauce for us — to find those people at the intersection between sports and cutting-edge tech,” said former MIT basketball captain Mike D’Auria, who led all business development at Second Spectrum until Genius Sports acquired the company in 2021. “Recruiting technical talent is really hard no matter what industry you’re in and then recruiting technical talent that also knows sports is an even smaller niche.”

When he became interested in using SportsVU’s player-tracking data to measure aspects of basketball that hadn’t yet been quantified, Second Spectrum co-founder Rajiv Maheswaran reached out to NBA contacts with a simple question: What would you like to know that right now you don’t? By far the most common answer was how to accurately quantify which pick-and-roll defenses work best against certain teams and players.

To extract answers from the endless rows of player-tracking data, Maheswaran and his staff built pattern-recognition algorithms that assessed not only whether a pick-and-roll happened but also what variation. Did the ball handler accept or reject the screen? Did the screener pop or roll? Did the on-ball defender fight over the top of the screen or go under? Did his teammate drop or show?

Second Spectrum’s ability to develop machine-learning systems that accurately identified and classified all those pick-and-roll actions was a game changer for their NBA clients. When facing Golden State for example, coaches could instantly find season-long data detailing which strategies had been most effective against a Stephen Curry-Draymond Green pick-and-roll and which players were best at executing them. Those coaches could then watch clips of each one of those Steph-Draymond pick-and-rolls if they wanted to verify the accuracy of the data.

Advertisement

“Knowing sport and technology, we were able to take this mountain of data and turn it into something that a head coach, a general manager, a sport scientist could use,” D’Auria told Yahoo Sports. “We could speak the language of the sport. Especially in those early days when there was a lack of trust, we would come in and say we’re going to help you do your job better. We’re going to save you time. We’re going to help you measure parts of the game that you care about.”

Camera-tracking systems were mounted in the rafters of every NBA arena by the start of the 2013-14 season. Second Spectrum continued to use machine learning to identify hundreds of complex basketball actions, from back screens, to pin-down screens, to isolations, to dribble handoffs, to closeouts.

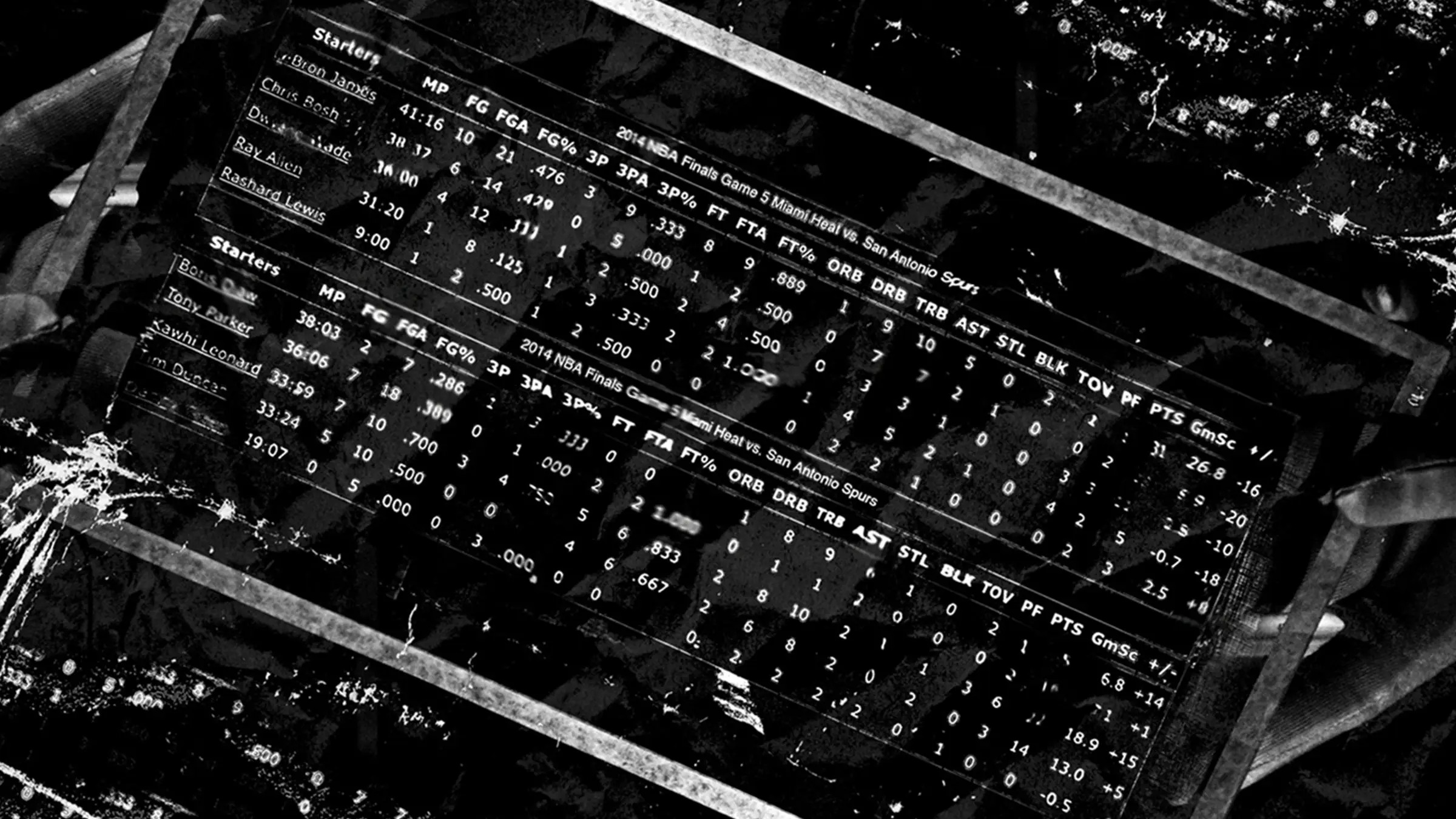

The savviest NBA teams responded by expanding their in-house analytics staffs so that they could use the new data to more effectively prepare for specific opponents. Detailed pregame scouting reports from former San Antonio director of basketball analytics Gabe Farkas and his colleagues contributed to the Spurs holding LeBron James and the high-powered Miami Heat to barely 90 points per game in the 2014 NBA Finals.

“We were tracking things around how their players’ shooting percentages fluctuated at various distances based on who was guarding them,” Farkas said. “It was informing who was defending LeBron, [Dwyane] Wade and [Chris] Bosh and how closely they were defending them on jump shots and post-ups.”

Advertisement

The Spurs also used player-tracking data the following offseason when assessing how lucrative a deal they were comfortable offering free agent point guard Tony Parker. Aware that Parker had a lot of mileage on his 32-year-old body, the Spurs studied how often the veteran point guard blew by his defender, how deep he penetrated into the paint and how that compared to his previous history and to his peers at his position.

“We didn’t want to pay for past performance,” Farkas said. “We wanted to pay for future expectations.”

The NBA’s player-tracking technology became even more sophisticated two years ago when the league announced a multiyear partnership with Hawk-Eye Innovations. Whereas previous tracking technology estimated each player’s location using a single point location, the Hawk-Eye system provides pose data, capturing 29 points on the human body.

A bumpy transition from the previous system to the new one drew a cacophony of complaints from analytics departments around the league, but the NBA is hopeful the Hawk-Eye system will allow teams to analyze and measure movement in new ways. Evan Wasch, the NBA’s executive vice president for basketball strategy, told Yahoo Sports the league is hopeful the 3D pose technology can be used “to augment the way we officiate games.”

Advertisement

Analytics have become an increasingly crucial part of NBA personnel decisions as motion-capture technology and machine learning tools have improved. Agents and team executives often arrive at contract negotiations with an array of advanced stats in their quiver, anything from how frequently the player secures a rebound in traffic, to how often a screen he sets leads to a made basket.

“It comes up in every conversation,” longtime NBA agent Mark Bartelstein told Yahoo Sports. “It’s not the end-all, be-all, but it’s part of the pie and it’s become more prevalent in recent years. Every team’s different in terms of how much weight they put in it.”

(James Pawelczyk/Yahoo Sports illustration)

Who does Cooper Flagg project to be?

It might be the most fiercely debated question ahead of this week’s NBA draft.

Advertisement

Which past or present NBA player is the best comparison for presumptive No. 1 overall pick Cooper Flagg? Is he the next Kawhi Leonard? Scottie Pippen? What about a better-scoring Andrei Kirilenko?

In 2023, four quantitative economists published a paper introducing a new way to answer those types of questions, one that they argue is more effective than both machine learning and linear regression analysis. Megan Czasonis, Mark Kritzman, Cel Kulasekaran and David Turkington took a mathematical forecasting system they had previously found successful in finance and applied it to the NBA Draft.

To forecast a potential draft pick’s NBA future, the economists start by compiling relevant data — anything from his height and weight, to draft combine measurables, to per-minute college stats, to his team’s conference winning percentage the previous season. They then use a series of algorithms to identify what previous draft prospects were most similar and to make a prediction based on the weighted average of how those players performed in the NBA.

“We had success with applications in the finance world, so we’re very confident in the methodology itself,” Czasonis told Yahoo Sports. “Once we were able to apply it to some sample data sets and look at the efficacy of historical predictions we would have generated, that’s when we realized this was something that could be valuable in sports.”

Advertisement

What Czasonis and her colleagues proposed is essentially a new approach to an old problem. Since the heyday of the APBRmetrics message board, analytics experts have been trying to concoct reliable methods of statistically modeling the NBA Draft to identify which prospects are going overlooked and undervalued.

The number of busts in every NBA Draft suggests that the perfect model doesn’t yet exist. It has been hard enough for basketball analytics experts to create a reliable all-encompassing player performance metric for NBA players. The draft is even harder to quantify in that way given the data limitations in college and international basketball, the age range of prospects and the disparity in styles of play and levels of competition they face.

“That’s why people say the draft is a crapshoot,” Farkas said. “You can try to adjust for the players’ ages. You can try to adjust for strength of schedule. You can try to adjust for different pace and style. But eventually you get something that is so mishmashed, so departed from reality, that it’s not necessarily usable anymore.”

While the draft will always be tricky, NBA executives can take solace that the league’s recent data revolution is trickling down to the college and international levels. Play-by-play data has become more reliable. Biomechanics evaluations for draft prospects are providing more consistent and accurate information. D’Auria anticipates the installation of player-tracking cameras in NCAA arenas before too long.

Advertisement

The NBA’s primary analytical battleground the next few years is likely to be turning the Hawk-Eye 3D player-tracking data into a competitive edge.

Could a team use it to better understand shooting mechanics and the crucial biomechanical elements of a successful jumper? Or to track fatigue during games and optimize how long players should stay on the floor without a rest? What about to quantify who the most physical defenders are in the NBA and which scorers are best able to play through contact?

Whatever path teams choose, don’t expect them to reveal any details publicly. That much was clear during one of the panel discussions at last year’s MIT Sloan Sports Analytics Conference when an audience member asked what the most underutilized advanced stat is.

Said Zarren with a chuckle, “I’m not answering that question.”

Advertisement

Atlanta Hawks assistant coach Brittni Donaldson echoed that.

“Yeah,” she said, “I’ve got competitors up here.”

Read the full article here