The official evacuation alert was issued from Parks Canada at 8 p.m. on July 22, 2024. By that time, Tahlon Sweenie, the Director of Golf at the revered Jasper Park Lodge Golf Course in the western Canadian Rockies, was already working with the resort’s management team to move 1,200 guests and staff off the course, out of the rooms and off the property—all in less than 80 minutes.

First and secondhand reports had been hitting people’s phones, creating general awareness that lightning strikes had ignited fires in the tinder-dry Valley of the Five Lakes to the south and that dry and gusty winds were pushing the fires closer.

Despite it all, Sweenie remained relatively calm. “I mean, I figured this was Jasper,” he says. “It’s a national jewel, right? There’s no way they’ll let the fire get this far.”

Shortly after the first alert, it was clear the fires were dwarfing the capacity of the crews fighting them. At 10 p.m., the alert changed to an order. The town was in immediate jeopardy, and 25,000 people (5,000 residents and 20,000 visitors) needed to evacuate, now. The highways leading south and east were engulfed in flame and smoke, leaving only one escape route, two-lane Highway 16 going west. By 8:30 p.m. there were thousands of cars trying to get on it. My wife and sister-in-law were part of that caravan. As the fires closed in, it took them four hours to drive a few miles. They were in the car for 16 hours before finding accommodation in British Columbia. All told, it was only good fortune and probably a bit of Canadian deference that meant no loss of life for anyone around Jasper that day.

The Parks Canada website would later report that, “as the wildfires continued to grow, they generated internal winds that accelerated wildfire growth at an aggressive rate. The fire-generated convective winds uprooted healthy, mature trees including their entire root systems and threw large embers as far as a kilometer ahead of the fire.” The winds picked up railcars and flung them into the Athabasca River miles downstream. Some flame plumes reached heights of 300 feet. It was so powerful and hot that it created a pyrocumulonimbus, a fire-generated thunderstorm.

/content/dam/images/golfdigest/fullset/2023/1/GD1025_FEAT_JASPER_02REV.jpg

SCORCHED EARTH: The course had been lined with between 8,000 and 9,000 trees. More than 7,000 were removed. (Photograph courtesy of Jasper Park Lodge)

Sweenie soon set up a kind of command center at the Banff Springs Hotel, a sister Fairmont property in the equally gorgeous town of Banff to the south. He was joined by Glenn Griffis, who soon after would be promoted to superintendent. After establishing that every staff member had landed somewhere safe, the two ran the irrigation system remotely, drenching the course in water until the fire arrived, roughly 20 hours after the alert. When the power went out, the irrigation went out. All they knew was that some of the buildings on the property were on fire and that the town was going up in flames, with the weight of Canada’s emergency response helpless to combat it.

It took three weeks for Parks Canada to declare the town of Jasper and surrounding areas safe enough for select staff and maintenance crew to return. Griffis’ home was burned to its concrete foundation. Sweenie’s was somehow spared. What the two men found on the golf course was beyond comprehension.

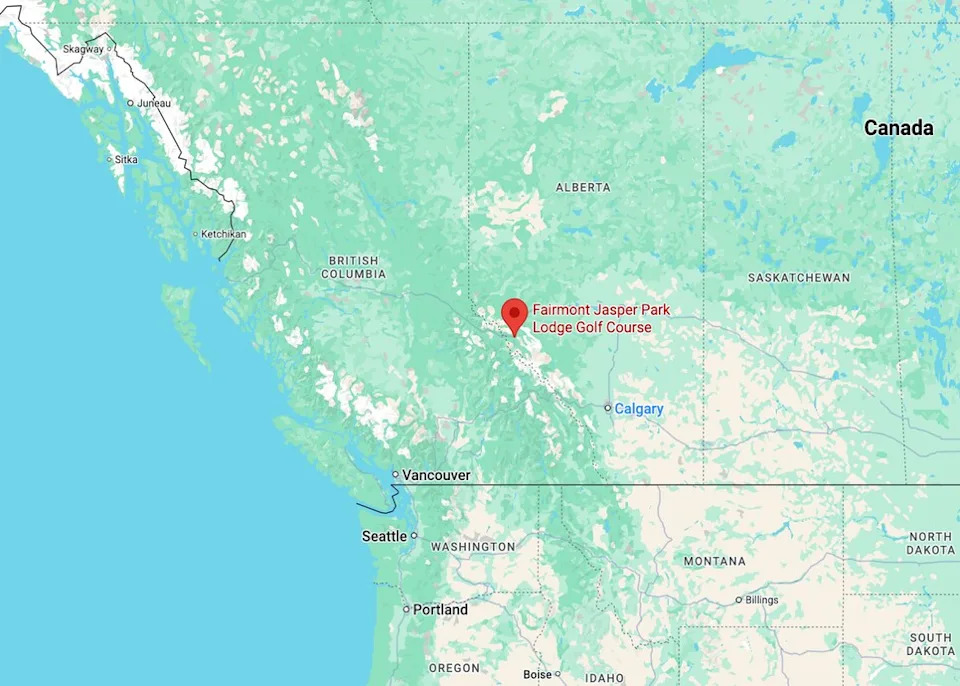

/content/dam/images/golfdigest/fullset/2025/10/jasper-park-lodge-google-maps-location.jpg

Golf Digest ranks Jasper Park Lodge Golf Course as No. 5 among the Best Courses in Canada. With all due respect to Stanley Thompson’s other great courses such as St George’s, Capilano and Banff, I think it is the best course ever built by the still-underappreciated Scottish-Canadian genius.

It had been lined with somewhere between 8,000 and 9,000 trees. We’ve all heard the term “scorched earth,” but rarely have we walked upon it. As Sweenie went hole to hole, there was almost not a single tree remaining alive. Either they were charred black flagpoles, or they had been uprooted and felled onto fairways, greens and into bunkers. It wasn’t the fire that had uprooted these 200-foot Douglas firs with 30-footwide root systems but cyclonic winds. “I don’t think there will ever be a more emotional four hours of my life,” says Sweenie of his first encounter.

On the 16th hole, a tree’s root system had ripped a foot-wide galvanized steel irrigation line from the ground, snapped it and twisted it like a piece of black licorice, leaving it groping 25 feet into the sky. Most of the course was covered in black ash and some spots were still smoldering on the charred greens. The site lost 90 percent of its tree cover, and most of the remaining 10 percent was centered around the Lodge itself (which, miraculously, survived, likely only because the golf course, drenched from the irrigation before it succumbed to the fire, acted as a natural break in the fire’s path).

/content/dam/images/golfdigest/fullset/2023/1/GD1025_FEAT_JASPER_07.jpg

MELTED MEMORABILIA: A Jasper Park Lodge logo ball found in the aftermath. (Photograph by Curtis Gillespie)

“I had no optimism, only sadness,” Sweenie says. “Sadness not just for myself, but for the golf world. I just had no concept of how we were going to open, in 2025, or 2026, or ever.”

Griffis walked the course not long after Sweenie on a grey, overcast day. “Obviously, it was shocking, the extent of the damage. The maintenance building was gone, just gone, the whole building and all 50 pieces of equipment. The only thing left was the cement pad footprint.”

Every structure, every sign, every shelter, every washroom, everything on the course was gone, too. A small bridge by the seventh hole and a bench on the 16th were all that remained. But Griffis noticed the grass wasn’t all dead. He scraped away black fried needles, pinecones and branches to inspect the greens. “A lot of the course was covered in a black carpet, and a lot of the grass was black, too, from burning needles that fell on it. Some of the greens just couldn’t handle the heat. But they weren’t all dead. It was running the irrigation system as long as we could that saved the golf course from being totally destroyed.”

Golf is an exercise in choosing what to see. We do this every time we step on a golf course.

Griffis imagined the following practical steps. 1: Liaise with Parks Canada to make the place safe to work at. 2: Get as much dead material as possible off the playing surfaces. 3: Borrow some equipment from somewhere to maybe think about cutting where possible. 4: Once the course was visible, identify what was alive, what was dead and what was urgent. 5: Get architect Ian Andrew, known as a kind of Thompson-whisperer, to come have a look to get his opinion on whether there was even any point.

“I have to admit, when I was driving in, I was pretty overwhelmed by the destruction,” Andrew says. He saw a golf course that was scorched to within an inch of its life, but in that inch was hope. Standing on the seventh green, amidst all the blown over and charred deadwood at the highest spot on the course, Andrew realized vistas he’d never had. He could see the 10th hole, the sixth hole. He could make out the topography better. Peaks in the distance that were hidden before were now visible. It occurred to Andrew that most of the trees that had been lost hadn’t been there when Thompson built the course a hundred years earlier. “Everything Stanley ever did was in the ground, and by the time we got to 7, I was thinking, this is doable.”

Turning to Sweenie and Griffis, Andrew said, “I can’t believe what I’m looking at. This might actually be better than before.”

/content/dam/images/golfdigest/fullset/2023/1/GD1025_FEAT_JASPER_05.jpg

BEFORE AND AFTER: Views of the bay have opened at the 358-yard No. 16. (First photograph courtesy of Jasper Park, second photograph by Kenneth Smith)

/content/dam/images/golfdigest/fullset/2023/1/GD1025_FEAT_JASPER_04.jpg

MORE: ‘How do you move on after losing everything?’: On playing through the deadly tragedy in Maui

The weather in the Canadian Rockies is unpredictable and a bit of a golf course maintenance nightmare, even in the best of times. But the trio knew that to have any hope of having a golf course in 2025, they’d have to get as much done as possible before the winter shutdown.

Of course, none of this was helped by the fact that Griffis and his team had no equipment. The only machines that didn’t get torched were two bobcats that happened to be parked offsite. Luckily, they were able to borrow a mower here, a blower there, and throw manpower at it. Sweenie worked on the insurance issues to see what could get replaced and how fast. Fairmont kicked in the money to get machinery while they waited for answers on the insurance.

Of the 1.5 million square feet of turf on the course, only about 75,000 square feet was irretrievably lost. A permit was obtained from Parks Canada to fell the most hazardous of the burned trees that were still standing. More than 7,000 burned trees were removed from the golf course; another couple of thousand were left laid down or standing to eventually fall and promote regeneration. They cut grass for the first time on Sept. 19, meaning there was two months’ growth on what had survived. Remarkably, some of the fairway grass had come back so robustly that it stood at fescue heights.

Most of the cleanup was completed by early October. Griffis rented a compressor to blow out the irrigation lines, which resulted in more pipes coming apart, but at least he had a fuller picture. Banff loaned JPL a sprayer, which allowed application of a winter fungicide. Then Griffis and his team tarped off every green, put up wildlife fences and took out all the destroyed fencing on the perimeter of the property. This took until the end of October. After a few more odd jobs, there was nothing left to do except wait for spring and see what reappeared when the snow melted.

Ancient mythology holds that fire purifies, and that destruction leads to transformation.

The Earth has the same amount of water that it had a a billion years ago. With average global temperatures rising, this has different implications depending on where you live. In western Canada, it has meant more regularly extreme temperatures at each end of the scale and more volatility. Across the planet, climate change means some places are getting hotter, some cooler, some wetter, some drier. This begs the question, is golf doing any active planning for the kinds of catastrophic events that a future of global warming will assuredly bring?

“The short answer is no,” Andrew says. “Typically climate change, wildfires, catastrophic events are not part of golf conversations. For sure, water use and limitations of applications have been for decades. Superintendents and some designers, me included, have written about that. Yes, we design around flooding. But there really hasn’t been a lot about fire.”

Wildfires can affect air quality across continents, but fire is not always bad. Naturally occurring forest fires are a necessary part of the cycle of growth and regrowth. Perhaps a reason fire gets talked about less than other climate impacts is that many prominent golf courses are less heavily treed and, in the case of most links courses around the world, not treed at all. But there are thousands of golf courses that have the potential to be devastated by wildfire.

/content/dam/images/golfdigest/fullset/2023/1/GD1025_FEAT_JASPER_10.jpg

HOT SEAT: Remains of a bench at No. 14. Virtually every sign and structure vanished. (Photograph by Ian Andrew)

Over the fall of 2024 and the winter of 2025, Sweenie, Griffis and Andrew mapped out a plan to resurrect the JPL golf course. “We knew we were talking about a 50-year plan,” Andrew says. “We were thinking about how to bring this golf course back to a place that might not get realized until long after we’re gone. I was thinking directly about how my grandchildren would feel playing Jasper.”

The deeper the trio got into the long-range planning, the more they began to focus on the potential gains, the opening of views, the health of the turf, the chance to reshape some of the green sites, even the unforeseen advantage of gaining new equipment and structures through insurance replacement. But primarily it was about trying to envision putting it back together note for note according to Thompson’s original vision. “The way I tried to explain it to Tahlon and Glenn,” Andrew says, “was to view it as a catastrophe, yes, but also as a chance to put everything in place for it to be the same a hundred years from now as it was in its best years before the fire.”

The course officially reopened on July 1 after having been closed for 344 days. In a ceremony prior to restarting play, Sweenie and other JPL executives spoke about the effort it took from so many to get back to this place. They honored local volunteer firefighters who hit ceremonial first tee shots. “The day was filled with so much emotion and anticipation,” Sweenie says. Some 80 people showed up for the ceremony. The tee sheet that first day had more than 200 names on it.

/content/dam/images/golfdigest/fullset/2023/1/GD1025_FEAT_JASPER_08.jpg

STILL GREEN: Steve Young, director of golf at sister-property Banff Springs, surveys damage with Sweenie. (Photograph by Ian Andrew)

Now that the destruction has come and gone, Sweenie, Griffis and others are noticing things they never saw before: the subtle changes in topography, the trails through the forest, the way Thompson used a small valley beside the seventh green that had long since disappeared due to tree growth, the way the third green is so elegantly shelved into an outcropping of rock that used to look simply like mounding. “It’s just so ironic in some ways,” Sweenie says, “that the year we’re celebrating our 100th anniversary we’re seeing the course probably closer to opening day than it’s ever been.”

In a way, golf is an exercise about choosing what to see. Most of the time we allow our eye to be directed rather than directing it by choice. We let the tree line, or a mound, or a water hazard force our sight line, which is often what architects want. But too often we don’t see the wildflower, the blackberry bush, the shape of the mountain in the distance. In a profound way, playing Jasper Park Lodge now is an exercise in choosing what to see. You can choose to see only the damage, the destruction, the blackened spars, the stark empty forest, the blunt reality of climate change and what it means for the future of golf. Or you can see turf that despite all has probably never been healthier, the newly opened views and sightlines, the now-visible topography that Thompson took such brilliant advantage of.

Or, probably best, you can choose to see both. You can choose the view that allows us to acknowledge that golf is a sport played in captivating locations which are deeply susceptible to the power of nature, a power we do not respect as deeply as we should. Climate change is accelerating and the impact it is going to have on all of us has consequences baked in. This will happen again elsewhere, as will other climate disasters related to our sport. We need to prepare.

/content/dam/images/golfdigest/fullset/2023/1/GD1025_FEAT_JASPER_09.jpg

344 DAYS LATER: GM Garrett Turta and Tahlon Sweenie (right) officially reopen the course on July 1, 2025. (Photograph courtesy of Jasper Park Lodge)

Ancient mythology holds that fire purifies and that destruction leads to transformation. Lightning cauterizes the wounds of the Earth in Seamus Heaney’s translation of Sophocles. There is no doubt that the fires of 2024 that destroyed Jasper will lead to a transformation. It took fortune and determination, but what will arise from those ashes may be better yet than what was before, though it will take decades to find out, which is precisely part of the mythology that makes our sport so unique and compelling. The fires of 2024 will be talked about decades from now at the JPL, but they will only be talked about because people will still be playing the course decades from now.

“It was a miracle that we were able to do it,” Sweenie says. “It just speaks volumes to the work Glenn and his crew put in, especially bearing in mind that they’re still working out of temporary buildings and using this assortment of borrowed equipment. But the pressure to put it all together and try to present something like the world-class golf course people remember has been enormous. We’re so proud of it, but the mental and emotional and physical strain on everyone has been intense. For all of us, this isn’t just a job, this is a passion, a vocation. And what Glenn has done is, honestly, inspirational for all of us, and he did it all amid losing his own house to the fire. But all of this is, in the end, only going to add to the aura of this place.

“This course took everything Mother Nature could throw at it,” says Sweenie, allowing himself a small smile. “And yet it’s still there.”

More From Golf Digest

Golf Digest Logo Forget Low & Slow: Snatch it back like Jon Rahm

Golf Digest Logo Golf Digest’s 50 Best Teachers in America (2026-’27)

Golf Digest Logo What’s In My Bag: Ben Griffin

Read the full article here