Nobody ever described Jake LaMotta as well as he once described himself. Or, actually, maybe describe is the wrong word. It’s more like he was confessing. Or possibly he was explaining something that took him a very long time to understand about himself. And even when he did finally understand it, he had limited success doing much to change it.

“I took unnecessary punishment when I was fighting,” LaMotta said years after retiring from the ring. “Subconsciously — I didn’t know it then — I fought like I didn’t deserve to live.”

Advertisement

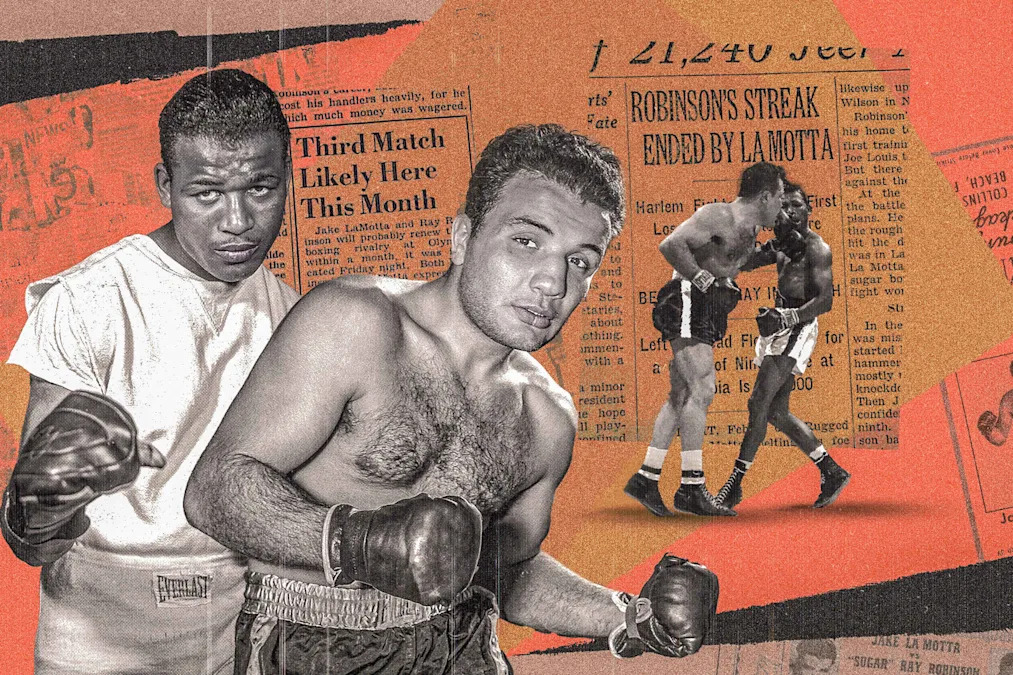

Imagine, then, how perfect it was for him to exist in the boxing world at the same time as “Sugar” Ray Robinson. In one corner was a man filled with such deep self-loathing that he went out in search of the punishment he felt sure he deserved. And waiting for him in the other corner was a man who loved himself completely and enthusiastically, one of the greatest fighters to ever live, a truly gifted dealer of that sanctioned punishment LaMotta longed for.

They couldn’t have realized at first how perfect they were for each other. But over the course of six fights across nine years — including two fights that took place in one month — they’d get plenty of opportunities to appreciate the fact of one another’s existence.

Even in the tumultuous world of prizefighting, LaMotta holds a special place in what we might call the Hall of the Unhinged. Born into an Italian immigrant family in 1922, he was raised primarily in the Bronx. He came of age there at time when, as he wrote in “Raging Bull,” a harrowing memoir that inspired the Martin Scorsese film of the same name, “everybody said the Depression was ending, though I couldn’t see it.”

To give you a sense of what LaMotta’s childhood was like, one day his father saw young Jake crying because some older boys had literally taken food right out of his mouth. His father was livid, but not at the boys who’d bullied his son. He slapped the child across the face and then put an icepick in his hand:

Advertisement

“He yelled at me, ‘Here, you son of a b****, you don’t run away from nobody no more! I don’t give a goddamn how many there are. Use that — dig a few of them! Hit ‘em with it, hit ‘em first, and hit ‘em hard. You come home crying anymore, I’ll beat the s*** outta you more than you ever get from any of them! Ya understand?’ He kept yelling and slapped me again, leaving my ear ringing and half-dead, but that phrase, ‘Hit ‘em first, and hit ‘em hard,’ stayed with me. It was the only good thing I ever got from my father, and later it always seemed to push the right triggers at the right time in my brain.”

One interesting thing about Scorsese’s film adaptation of LaMotta’s life is that it skips over his childhood entirely. The movie is concerned only with the man and not the boy, which is why it begins with LaMotta already a successful boxer in early adulthood. But what becomes clear from LaMotta’s memoir is that, especially in his case, the boy was very much father to the man.

The most important event of LaMotta’s early life, at least in his telling, was the time he beat a local bookie nearly to death. Then a teenager living an impoverished life in a Bronx neighborhood where crimes of one sort or another were just part of the scenery, LaMotta claimed he attacked a bookie named Harry Gordon. He came up on him from behind one dark night with a lead pipe in hand, thinking to rob the man of the cash he was known to carry while collecting bets throughout the neighborhood.

“One bop, I figured, and Harry would go down, and there I’d be with his take for the day … I never was so nervous before in all my life. I came up behind Harry in the dark between the street lamps so quick and so quiet that he never even had a chance to turn, and I hit him with the pipe over the back of the head and pushed him through one of the gaps in the fence to the vacant lot. But he didn’t go down. He was bent over and moaning and I thought I’d hit him hard enough to flatten him, but no, he started to turn. And then I got so mad at him because he was still on his feet, I lost my head. I wanted to kill him I was so mad that he was still up, and I began to hit him again and again. And finally he collapsed.”

LaMotta reached inside the man’s coat, took his wallet, and then ran. He told only one person what he’d done — his best friend Pete Savage, who co-authored his memoir. (In the film version, Pete gets turned into LaMotta’s brother Joey, played by Joe Pesci.)

When Pete opened the wallet, he found no money in it. Even worse, the next day he showed LaMotta a newspaper story that said Harry Gordon had been found beaten to death in an alley at the age of 45. (The newspaper had gotten it wrong; Gordon wasn’t actually dead, only badly beaten. LaMotta would meet him again years later, a shocking surprise followed by a great relief to find out that he wasn’t a murderer after all.)

Advertisement

LaMotta initially insisted that he felt nothing upon hearing this news, but as time passed the guilt ate at him. When he was later arrested on an unrelated burglary charge and sentenced to 18 months in a reform school, he was almost pleased about the outcome. It meant he’d escaped justice for the murder. By the time he was let out, he reasoned, the heat would have died down. He’d get away with this crime in the end.

He found it tougher to escape his own conscience. He internalized the idea that he was a bad person who did bad things, and therefore had bad things coming to him in return. He seemed to regard himself as helpless to change this, lacking all agency.

He also, according to his own version of events, continued to be a destructive, chaotic force on all those around him. (His memoir is truly a tell-all in a way few sports autobiographies ever are. In addition to telling the story of beating of the bookie, LaMotta admits to at least two rapes and several domestic violence incidents, a couple of them nearly fatal, while also opening up in an oddly flippant fashion about his struggles with impotence and intense sexual insecurities.)

This feeling that he was a monster who deserved only misery and righteous comeuppance haunted LaMotta, while also serving as a bizarre motivator in his fighting career. For instance, take his account of his first attempt at boxing in reform school, where he faced a larger, more experienced opponent who thrashed him in a sparring session:

“I still don’t know how to explain it, but I felt that if I didn’t destroy him, he would destroy me, and that for some reason he had a right to destroy me. And that enraged me more — the fact that somehow I felt he had that right. And that’s what I went out to fight, to kill.”

LaMotta’s time in reform school ended up being a net positive in his life. For one thing, he found that he had a friend from the old neighborhood who was already there. That friend was Rocky Graziano, who would later become middleweight champ in 1947. With Graziano’s help, LaMotta began to train seriously as a boxer for the first time while he was locked up. Once he was released, he knew what he wanted to do with his life. He was going to make it as a pro boxer or die trying. He just didn’t know then all that the sport would demand of him.

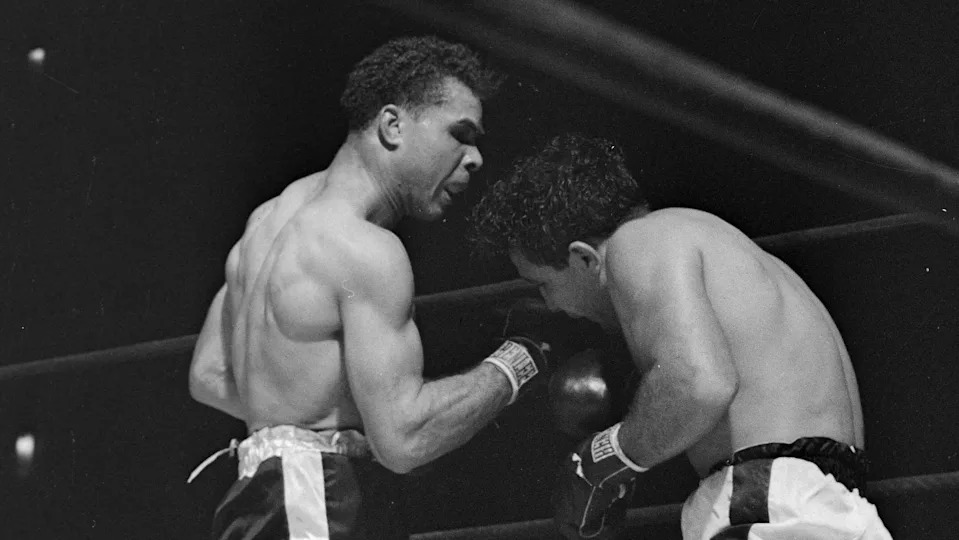

Feb. 14, 1951: Jake “Raging Bull” LaMotta in the 13th round of his final fight with Sugar Ray Robinson. Chicago, Illinois.

(Underwood Archives via Getty Images)

Everything was going right for Walker Smith Jr. when he first ran into LaMotta in 1942. He was undefeated in 35 pro bouts, which didn’t even include an extensive amateur career that saw him win New York Golden Gloves titles at both featherweight and lightweight, all without ever losing a fight or even coming close. His greatest achievement through much of his amateur career, however, was that he did it all without his mother ever finding out that he was boxing.

Advertisement

The name thing helped. You could even say it was fortuitous. Because while young Walker’s mother didn’t want him fighting, she did allow him to work out with the local boxing coach from the Police Athletic League. She even sometimes let him travel with his teammates to boxing events, which is what he was doing when, one magical night, there was an opening on the fight card. They needed someone to step in, and there was Walker Smith Jr. without any plans for the evening.

What he also didn’t have was a membership card with the Amateur Athletic Union, which was required in order to fight. So his coach pulled out a card that belonged to another boy who’d signed up and then apparently quit. That boy’s name happened to be Ray Robinson.

The “Sugar” part got added later, once it became clear to all who saw him that he was a special fighter, a true natural who made the task of taking another man apart in a boxing ring look effortlessly smooth. He’d always had great footwork. He used to earn extra money as a kid in New York City by going down to the theaters and dancing for coins when audiences filed out during intermission. But now, after more than 100 bouts between his amateur and professional work, he’d developed into the total package.

Robinson could punch with power but also technical precision. He was one of the only fighters who, according to boxing writer and historian Bert Sugar, “could deliver a knockout blow going backward.”

Advertisement

“He boxed as though he were playing the violin,” observed New York sports writer Barney Nagler.

He had an iron chin and was never knocked out — not once, even when fighting well above his natural weight class — in over 200 pro fights. The closest he came was in a light heavyweight title fight with Joey Maxim on a scorching day at Yankee Stadium in 1952, when he collapsed without being hit in Round 13 and could not rise. Being in the ring that day, according to referee Ruby Goldstein, felt like “being roasted alive.” It was the biggest win of Maxim’s career and he earned it simply by staying upright in the punishing heat.

But Robinson didn’t just excel at the fighting portion of the business. The man also had style. Harlem residents could always tell when he was present at his nightclub (creatively named Sugar Ray’s) because his custom pink Cadillac would be parked out front. He owned almost an entire block on Seventh Avenue, north of 123rd Street. There he opened a real estate office, a barbershop and a women’s clothing boutique for his wife Edna May.

Advertisement

At the Salem Methodist church that Robinson and Edna May attended, the couple were superstars, as Wil Haygood writes in his biography, “Sweet Thunder: The Life and Times of Sugar Ray Robinson”:

“If told that Sugar Ray and Edna Mae were coming to church on a certain Sunday morning, the minister in the pulpit was careful not to begin until the couple arrived. Many strained to see the cut of their attire. (Robinson had a habit of stopping cold just inside the church doorway before beginning his stride to his seat.)”

He popularized the term “entourage” to refer to a celebrity’s retinue of handlers and hangers-on after he overheard a steward on a ship to Paris explaining to his coworker that the large group of Black people onboard was “the boxer, Sugar Ray Robinson, and his entourage.” (Robinson loved the term and insisted thereafter that the press use it to refer to his omnipresent pack of friends and lackeys.)

Once in Paris, he was an immediate star among the French, with some cafes selling “Sugar Cakes” in his honor. A report in the Chicago Tribune claimed that Robinson had “captured Paris more completely than Hitler.”

Robinson also became one of boxing’s first proven TV draws in an age where televisions were still beginning to transform into a standard home appliance. Big events, such as Robinson’s last fight with LaMotta, were known to increase TV sales at department stores in the days leading up to the fight, and were heavily advertised in store windows for this reason. (Robinson was keenly aware of the value of TV exposure. In one fight, he was said to have asked a reporter between rounds if he thought the action looked good for TV so far. When informed that the fight wasn’t being televised, Robinson muttered a curse and then got up and knocked the opponent out in the next round.)

Advertisement

In short, as a smooth technical boxer and stylish celebrity who reveled in the attention he was certain he deserved, Robinson was everything that the brutish slugger LaMotta was not. But when they fought for the first time in 1942, they both had the same problem: Neither was a champion, despite excellent professional records.

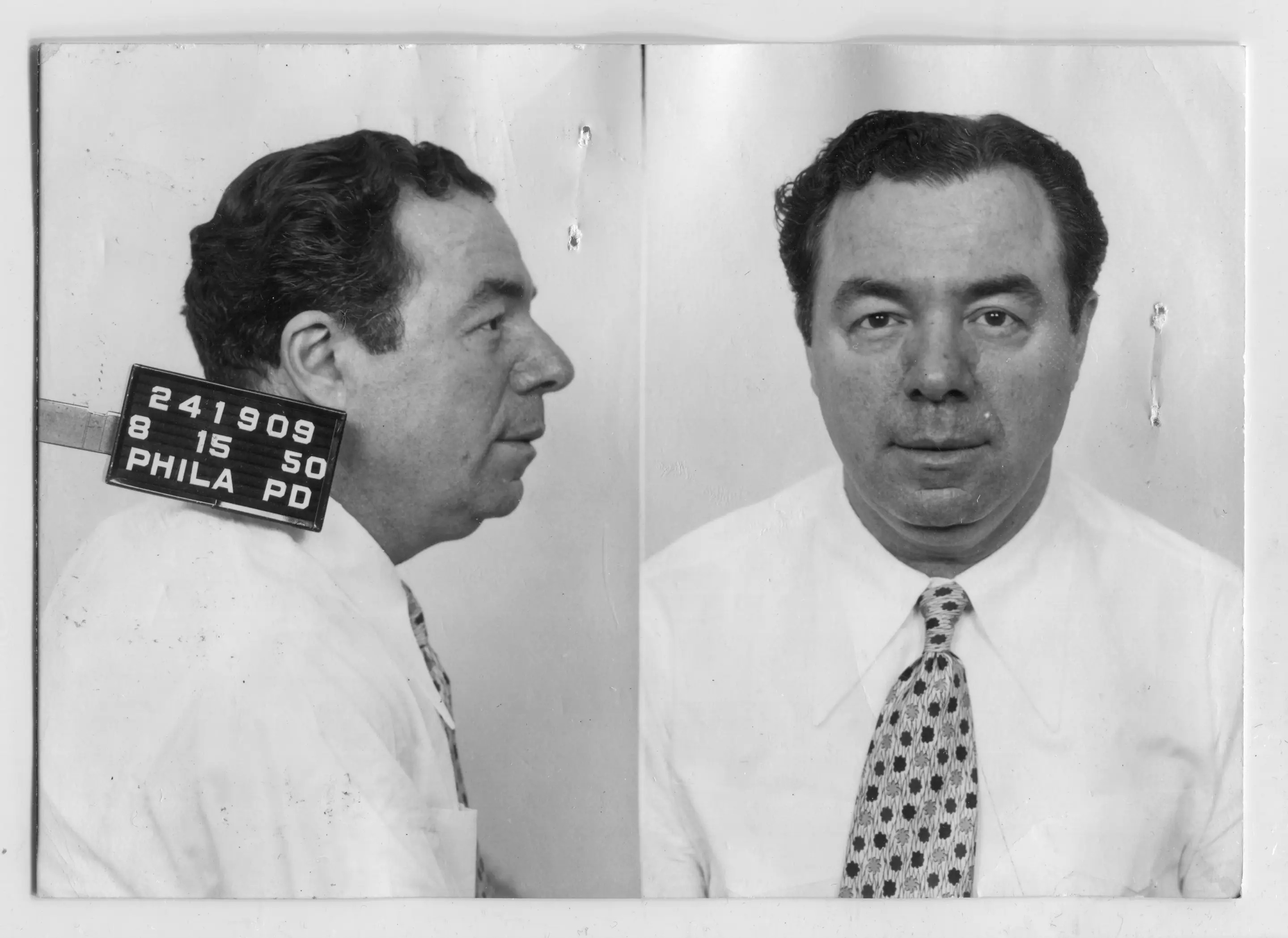

And for this, both blamed the mob — specifically organized crime figures like Frank “Blinky” Palermo of the Philadelphia mob, and Frankie Carbo in New York, who was sometimes referred to as “the czar of boxing.” They were known to own or control many fighters and managers, particularly in divisions like welterweight and middleweight.

Robinson and LaMotta would choose different ways of dealing with this problem. But each had to ask himself just how badly he wanted to be a champion. And what he was willing to sacrifice to get there.

Nov. 27, 1950: Sugar Ray Robinson yells at his opponent, Jean Stock, to climb to his feet and continue the fight. Paris, France.

(PA Images Archive via Getty Images)

It might sound like typical conspiracy theory stuff now, but in the 1930s and ‘40s — even well into the ‘50s — mob figures in New York, Chicago and Philadelphia were practically running the sport of boxing in America. Gangsters like Owney Madden and Bill Duffy were widely believed to have crafted the career of heavyweight champ Primo Carnera, cutting the towering fighter almost entirely out of the profits in the process.

Advertisement

Coming up in New York’s boxing gyms, LaMotta had plenty of chance to see the mob’s influence at work. As he writes in his memoir:

“Back in those days there were a lot of gyms for boxers, it was no trick at all to get started. Managers, by and large, were a collection of thieves and almost to a man tied in with the mob, but they were always on the lookout for a promising kid, because even if the kid wasn’t destined to become a champ, still if you’re taking a third or a half of his purses, besides what you can steal, you can make money out of even a second-rate fighter. … And I also noticed that around the gym all the time there were the mob guys, for the very simple reason that there’s always betting on fights, and betting means money, and wherever there’s money there’s the mob. If you paste that inside your hat it will explain a lot of things to you and maybe even save you some trouble.”

As a teenager, LaMotta’s orbit had been drawing ever closer to the mob, particularly the Lucchese crime family. He did some light breaking and entering, once held up a dice game as a teenager on a tip from some underworld figure, and was beginning to become a known man to his friendly neighborhood gangsters.

But after emerging from reform school with dreams of boxing glory, he’d resolved to resist any association with the mob. He knew from experience how one thing could lead to another. Once the mob had its hooks in you, perhaps by doing you a small favor to help your boxing career, it would never let you go. As LaMotta repeats often in his memoir, he wanted to make it on his own.

But once he became a top middleweight, the lack of a title shot became more and more glaring. Reporters often asked LaMotta why he thought he was being denied the opportunity.

Advertisement

“The newspaper guys knew the answer as well as I did — at least some of them did — that I wouldn’t play ball with the mob, that I wouldn’t take on a mobster as a front man for a manager, which was the main thing they wanted. What the newspapermen wanted was for me to say that. It doesn’t make any news if a newspaperman knows it and says, but if the world’s number-one middleweight says it, then it’s surefire for the front pages.”

The reason he refused to say it publicly, LaMotta insisted, was because he felt it might slam the door on his title hopes for good. In those days, to even acknowledge the existence of organized crime was, at the very least, a serious breach of etiquette.

Robinson also wanted to steer clear of organized crime figures, but for him it seemed to spring less from a fear of being sucked into the mob’s whirlpool of influence and more about steering his own career. More than many other boxers at the time, Robinson knew his worth and wasn’t afraid to push for it. As Jeffrey Sussman writes in his book, “Boxing and the Mob: The Notorious History of the Sweet Science”:

“Robinson was known as one of the toughest negotiators in boxing, one of the few boxers who negotiated his own deals. An hour before a fight, he would often refuse to fight unless certain additional conditions were met in his contract. He would drive frustrated promoters to rage against him, but Robinson would always remain calmly adamant. He knew his drawing power, and he knew that his demands would invariably be met.”

In his Robinson biography, Haygood notes that Robinson was “the first Black athlete to largely own his own fighting rights, and the first to challenge radio and TV station owners about financial receipts … constantly battering back the belief that the athlete — especially the Negro athlete — was an uninformed machine.”

Advertisement

The extent to which he maintained his own personal firewall with the mob has been debated. While Robinson was never credibly accused of throwing fights, there were occasional claims that he’d agreed to carry certain opponents in order to appease gambling interests that wanted to see a fight go the distance.

In his book, “The Devil and Sonny Liston,” Nick Tosches alleges that Robinson had accidentally knocked out Al Nettlow in a fight that was supposed to go to the judges. That same night, Tosches writes, Robinson “went to the newsstand where mobster Frankie ‘Blinky’ Palermo hung out, and he tried to explain what had happened. ‘It was an accident,’ he told Blinky. ‘I just happened to catch him.’” The mob is said to have let Robinson off the hook for that mistake.

Aug. 15, 1950: Mug shots of Philadelphia-based mobster Frank “Blinky” Palermo. He was later investigated by the 1960 Kefauver Committee, which examined the organized crime world’s involvement in boxing.

(PhotoQuest via Getty Images)

The first time Robinson and LaMotta met, at Madison Square Garden in the fall of 1942, both were still struggling to make it on their own in boxing. Robinson had moved up from welterweight, having all but cleaned out that division without earning a title shot. LaMotta was one of the bigger fighters in the middleweight class, and some thought his size and strength would give Robinson problems.

Advertisement

Dan Burnley, writing for the Amsterdam News, questioned Robinson’s move up in weight:

“Robinson has an alarming tendency to get in close with rough, tough, bear-like individuals when there is no need to do so, mainly because Sugar likes to prove to himself and to the fans that it makes no difference to him whether he’s punching at a distance or mauling in the close-ups.”

But in that first meeting, Robinson’s speed and footwork proved superior to LaMotta’s strength and aggression. LaMotta would later recall it as a frustrating fight. Every time he got close to landing cleanly, Robinson slipped away. As became routine in their series, LaMotta began to have more success later in the fight as Robinson slowed, but the first fight was still a clear win for Robinson.

What helped turn it into a true rivalry was their second meeting four months later in Detroit. World War II was raging in Europe and the Pacific, and Robinson was expected to be inducted into the Army the following month. (One account suggested that he’d been warned in advance that a draft notice was coming, possibly by mob figures who wanted to insinuate that they’d helped speed this along to punish Robinson for his lack of cooperation.)

LaMotta was exempt from military service due to a childhood mastoid operation on his ear, which he at times attributed to a consequence of his father’s abuse, while at other points blaming the cold and dreary conditions of the Bronx tenement he grew up in. But there were rumors that, with a hitch in the Army forthcoming, Robinson had been even more enthusiastic than usual about enjoying the company of multiple women while he was still a civilian.

Advertisement

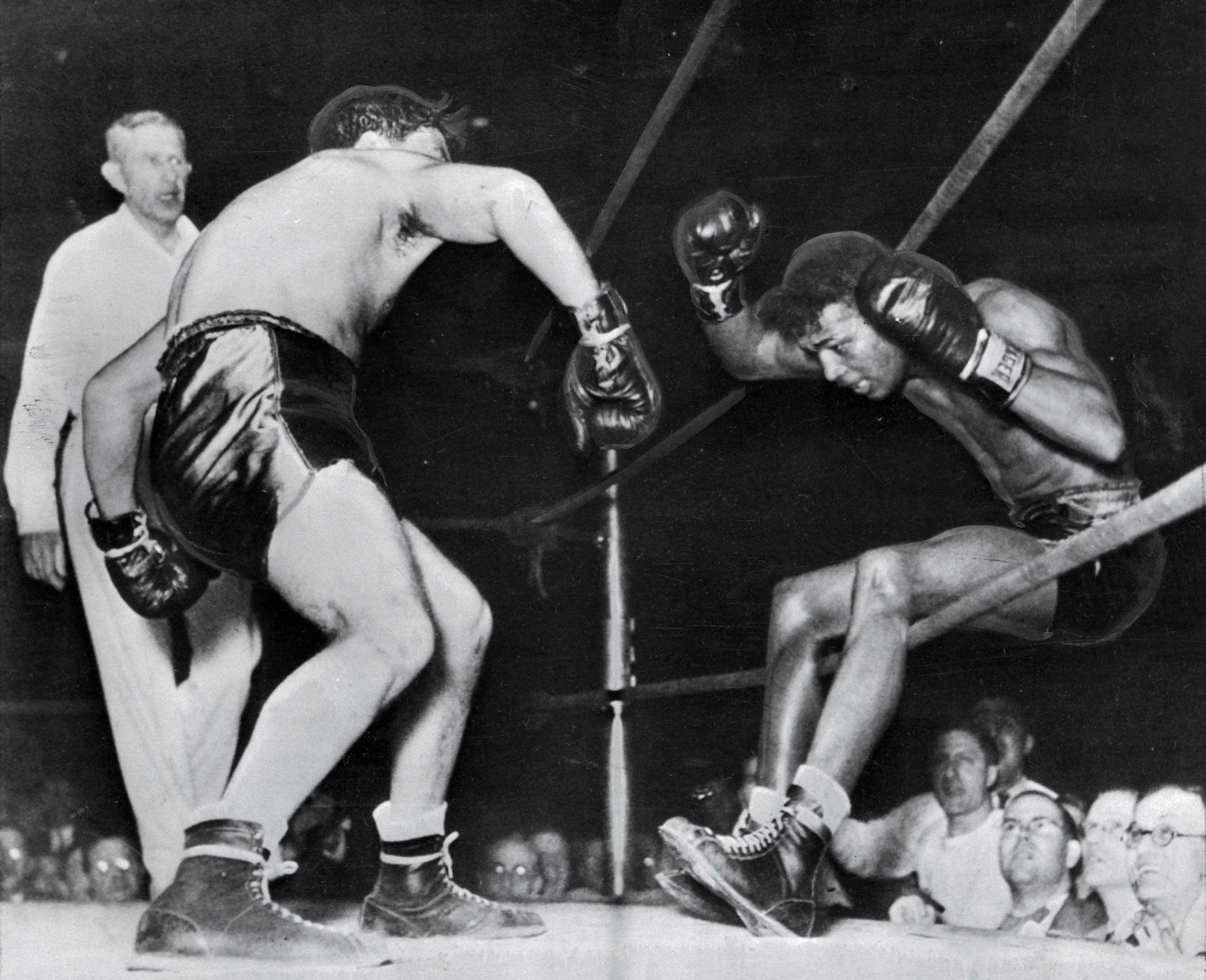

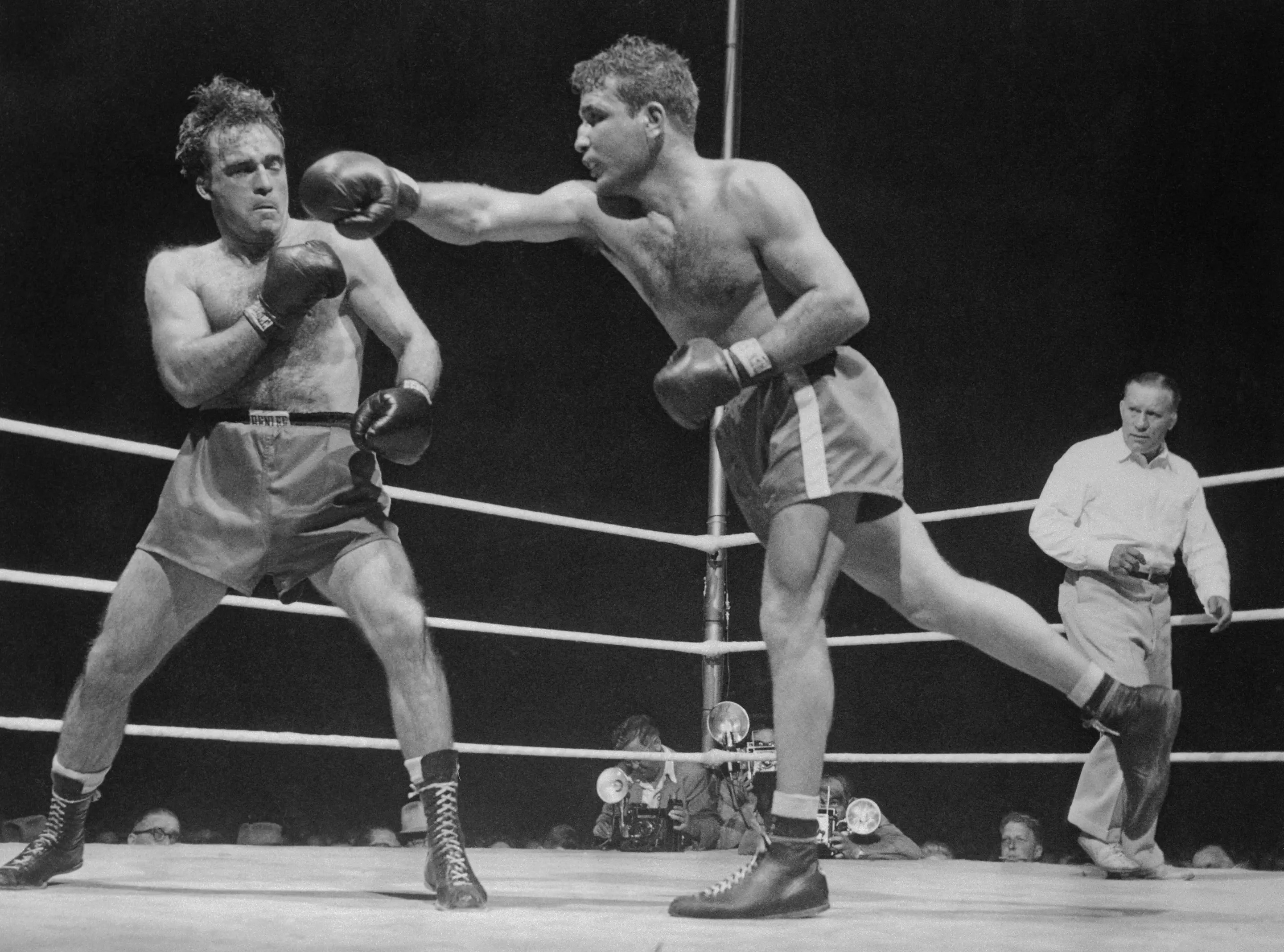

So when LaMotta finally caught up to Robinson that early February night in Detroit, knocking him through the ropes in the eighth round with a hard shot to the body followed by a hook to the head, there were those who were ready to attribute it to Robinson’s unfocused preparation.

Feb. 5, 1943: Victorious in 129 successive fights, including 40 as a pro, Sugar Ray Robinson falls through the ropes of a Detroit ring, under the impact of Jake LaMotta’s fists. Robinson got back in the ring, but lost the decision in 10 rounds.

(Bettmann via Getty Images)

LaMotta seethed at that suggestion. He’d prevailed with the help of a smarter game plan, he insisted. This time, instead of swinging at Robinson’s head and hitting nothing but air, he went after the body. He even had a member of his team whistle at him every time he went upstairs too much, reminding him to stick to the game plan without ever having to say it out loud. LaMotta put his 16-pound weight advantage to work in close, and it eventually wore Robinson down and set up the shocking knockdown.

Robinson had managed to climb back in the ring and was up in time to beat the count, but when the judges’ scorecards were read, they all agreed — LaMotta had given Robinson his first loss in any fight, amateur or pro. The New York Times headline following the bout read: “END OF ROBINSON STRING SHOCKS WORLD.”

Advertisement

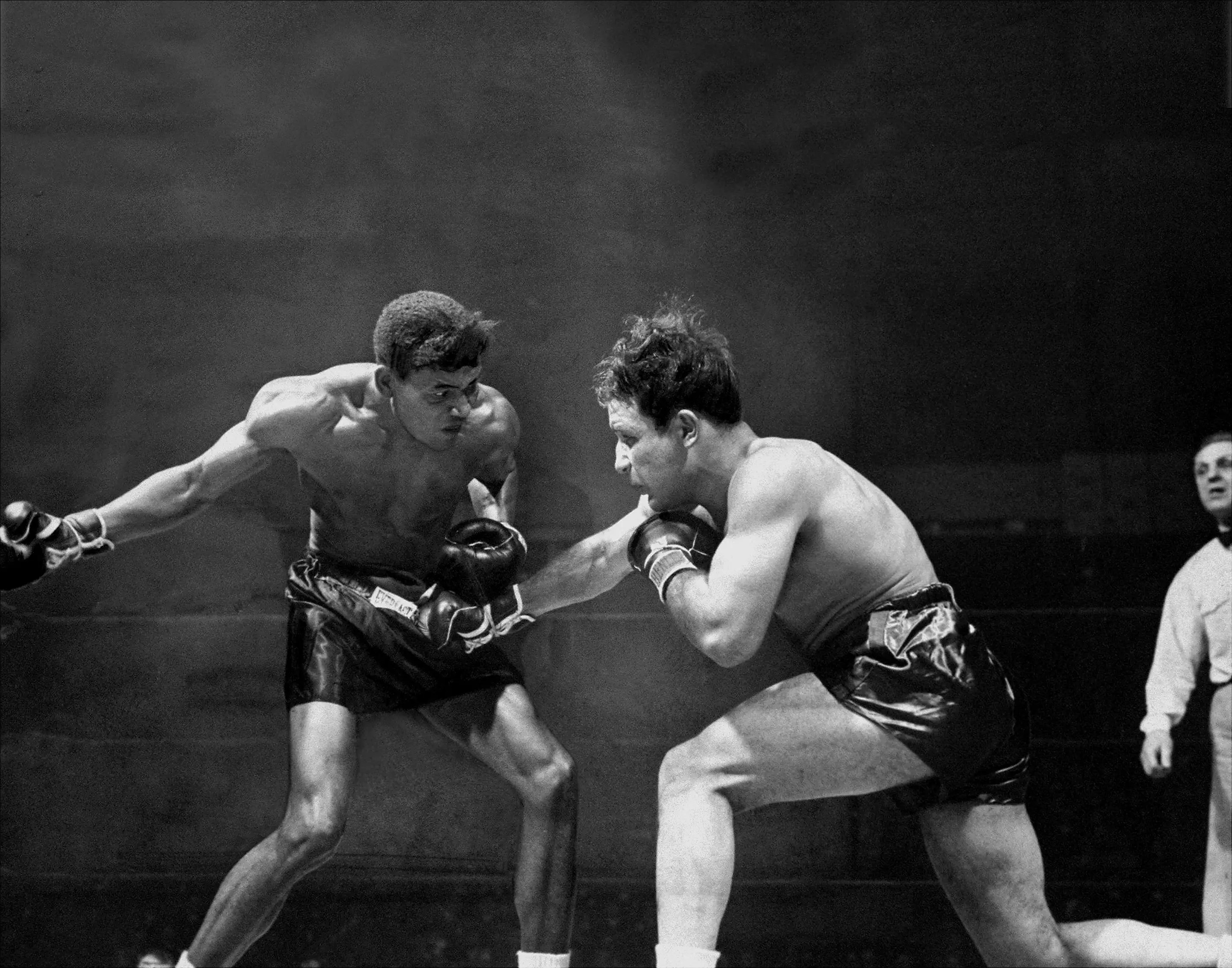

A third fight was almost automatic. And with Robinson due to begin military service soon, there was no time to waste. Both fighters agreed to meet again just three weeks later. Incredibly, that wasn’t enough activity for Robinson, who squeezed in a quick warm-up fight with Olympic silver medalist “California” Jackie Wilson in between the two Lamotta fights. (LaMotta was ringside to watch it. He’d already beaten Wilson a month and a half prior, who he later said came into their fight as a 4-to-1 favorite and “went out of it a sadder but wiser man.”)

Their trilogy fight would take place back in Detroit, in the same building where Lamotta and Robinson set an attendance record with more than 18,000 paying customers just a few weeks earlier. This time, it was said, Robinson wasn’t taking LaMotta lightly. But with the city of Detroit now conducting regular air raid drills and the latest news of the war dominating headlines, LaMotta was concerned going in that Robinson’s impending military service might sway the judges in a close fight. And, after he’d scored a late knockdown but still lost the decision in that fight, he never stopped believing this was the root cause.

As LaMotta wrote in his memoir:

“I lost the third Robinson fight. That’s not right. I didn’t lose it, he got the decision. You can ask anyone who was there, or if it means that much to you, you can read the newspaper stories. I know the date of this fight, it was the last week of February in 1943 and Robinson was going into the army the next day. I’m not knocking him on it. I would have done the same thing in his shoes, but he got every newspaper inch there was about the story of this brave boy off to fight for his country. He didn’t fight up to his best in the ring that night, but he got a decision by one miserable vote after I decked him once.”

LaMotta wasn’t the only one who felt the judges had gotten it wrong. The Detroit News wrote that when the decision was announced, the “howls of protest” from the crowd were so loud and prolonged, the ring announcer had to give up trying to be heard over them and wait it out instead.

Feb. 26, 1943: Sugar Ray Robinson winds up a punch to throw at Jake LaMotta.

(New York Daily News Archive via Getty Images)

The Robinson feud begot a big boost to LaMotta’s popularity. In New York, where the mob had a tighter grip on the fight game, he’d struggled to earn big purses at times. After coming west and building up his profile against Robinson, he was now earning big money — and spending it as freely as Robinson did.

Advertisement

Still, none of it got him a title shot. World War II came to an end. He fought Robinson two more times over eight months in 1945, losing both via decision but feeling at least slightly robbed each time. (“You don’t keep fighting unless the fights are close,” LaMotta said years later.) The possibility that his athletic prime might pass him by without ever getting a chance to fight for the middleweight title began to seem frighteningly real.

And so, in 1947, LaMotta agreed to break his own rule. He’d play ball with the mob after all. But what they asked of him was even worse than he’d imagined. If he wanted a chance to become champion, they told him, he’d have to throw a fight to Billy Fox, a mob-controlled fighter whose entire career had been essentially a sham.

LaMotta agreed to lose, but did so extremely poorly. Instead of feigning a knockout blow, he simply dropped his hands, leaned against the ropes, and let Fox tee off on him until the referee stepped in. In The New York Times, writer Arthur Daly observed: “A curious pride kept [LaMotta] vertical. He was willing to sink low enough to be a party to a fraud, but not willing to sink to his knees.”

Nov. 14, 1947: Billy Fox (L) lands a right uppercut on Jake LaMotta during their scheduled 10-round bout at Madison Square Garden. LaMotta infamously threw the fight in the fourth round.

(Bettmann via Getty Images)

The sham fight fooled no one. The crowd showered him with boos. Even Fox, who’d been oblivious that all the fights he was winning were fixes, began to catch on after the LaMotta fight. (He soon lost his stomach for fighting and was abandoned by his mob handlers, who’d kept most of his winnings. He become homeless, then later died penniless in a state hospital. The LaMotta fight, Fox told Sports Illustrated, “made me feel despondent, downhearted, disgusted.”)

Advertisement

The state athletic commission in New York withheld the purses and called LaMotta in for a hearing to answer the fix allegations. Fortunately for LaMotta, he’d covered his bases. He visited a doctor in the weeks before the Fox fight and got diagnosed with a ruptured spleen. His poor performance, he argued, was simply a result of trying to fight through a serious injury, as boxers routinely did.

No one believed this, but since the commission couldn’t prove anything it settled for fining and suspending LaMotta for failing to disclose the injury.

Still, the mob made good on its promise — at least once enough time had passed to make it seem not quite so obvious. In 1949, LaMotta finally got a crack at middleweight champion Marcel Cerdan. He later said that even after the thrown fight he still had to pay $20,000, which he assumed went to Cerdan’s camp, in order to get the fight. This meant that even with his purse for the fight factored in, LaMotta essentially took a financial loss on the title shot he’d pined for his entire career.

He got what he wanted, though. Cerdan went down on a clumsy slip early in the fight and seemed to suffer a shoulder injury when he hit the canvas. He still fought bravely with one good arm, but LaMotta pummeled him until the fight was finally halted after the ninth round. LaMotta was a champion at last, even if he had to practically sell his soul to get it.

Advertisement

A rematch was planned, but before the fight could happen Cerdan was killed in a tragic plane crash that took the lives of everyone on board. LaMotta held onto the title for the next two years — until his old friend “Sugar” Ray came calling one last time.

June 16, 1949: Jake LaMotta (R) throws a right hand at Marcel Cerdan of France in their middleweight championship fight in Detroit. LaMotta took the title with a knockout in the 10th round.

(Bettmann via Getty Images)

Later they called it the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre. Feb. 14, 1951. Chicago Stadium. Unlike previous installments, this final episode in the fierce rivalry between Robinson and LaMotta broadcasted to an audience of millions.

“Never before has any event been heard and seen by so many people, not only here in America but right around the globe,” commentator Ted Husing said at the start of the broadcast, sponsored by Pabst Blue Ribbon.

Advertisement

Robinson had won the welterweight title some five years earlier. He’d finally gotten his title shot the old-fashioned way: By becoming too popular and too lucrative for boxing’s power brokers to deny.

Now he was coming for LaMotta’s middleweight belt in a bout billed as a “battle of the champions.” The fact that Robinson had dominated the series with four wins and only one loss against LaMotta did not diminish public fervor for the clash. But unbeknownst to the vast viewing audience, “The Bronx Bull” was in a bad way.

Making the middleweight limit had never been easy for LaMotta. He later wrote that boxers lost weight the same way regular people did: Torture. Now he was almost 29 years old, had fought more than 100 pro bouts in a decade, and his body labored to make the 160-pound limit.

“I must have known that defeat was coming, even though I wouldn’t admit it to myself, because I even began to think about the possibility of hedging the bet of ten thousand dollars that I’d made on myself,” LaMotta wrote in his memoir. “Then I thought, Christ, that’s all I’d need, to have something like that on my record. And that is not the sort of thing that can be kept quiet.”

Advertisement

He told his brother to bring him a bottle of brandy, something he’d never done before a fight. It was for “false courage,” he recounted later. Deep down, he knew this version of LaMotta was in for a bad night against this version of Robinson.

LaMotta started fast, trying to repeat his earlier success when attacking Robinson’s body. But soon Robinson began to take over, punishing LaMotta with power punches, as if determined to end this rivalry with a knockout.

Robinson admitted later that he was amazed by LaMotta’s ability to absorb punishment in the fight. “The more I kept punching, the more determined he seemed to stay on his feet,” he said of LaMotta.

Advertisement

But by Round 13, LaMotta was spent. Robinson saw his opportunity and unloaded, battering LaMotta against the ropes. LaMotta was cut and bleeding badly, but instead of using his hands to protect his face, he reached out to grab the ropes, holding himself up out of sheer stubborn will — and leaving himself open to a terrible beating in the process.

As he recalled later, it was “about as bad a beating as I’ve ever had.” He took it, he said, because he “just wouldn’t give the son of a bitch the satisfaction of knocking me down.”

Finally, referee Frank Sikora stepped in to save LaMotta from himself. Robinson was the new middleweight champion of the world. But the savagery of the fight’s last few minutes made an impact on the viewing audience, many of whom were not entirely accustomed to the ways of the fight game.

An editorial on the front page of the Indianapolis News called the televised fight “a sickening tribute to brutality.” New York Post writer Al Buck praised LaMotta’s toughness, noting that “the bleeding, bruised and battered Bronx Bull was still on his feet, but nobody would want to see that slaughter again.”

Feb. 14, 1951: Ray Robinson presses his attack to the head of Jake LaMotta in the 13th and final round of their legendary six-fight series. The brutal beating became known as the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre.

(Bettmann via Getty Images)

They wouldn’t have to. Robinson’s TKO win propelled him to new heights of fame and popularity, while the beating LaMotta took effectively ended his career, even if he went on to fight 10 more largely uninspired bouts before finally retiring in 1954.

Advertisement

His second wife, Vikki, said later that LaMotta was “never the same in or out of the ring again” after that final fight with Robinson. “Physically and psychologically,” she said, “Sugar Ray Robinson destroyed him.”

After LaMotta retired, he and Vikki moved to Miami Beach, where he opened a nightclub. (Proving he could be as unimaginative as Robinson, he called it Jake LaMotta’s.) He burned through money, drank like a fish, and tried to bed just about every woman in South Florida. Vikki soon left him, and not long after that he was arrested on a charge of promoting prostitution after a 14-year-old girl said LaMotta had introduced her to men in his bar.

Even in a memoir in which he admits to all manner of awful crimes, LaMotta proclaimed innocence on this charge in a fashion that reads today as entirely unsympathetic:

“There was this fourteen-year-old broad. That’s right, fourteen. They get ripe early down south. She testified at the trial that she had been in my place twice. Let me repeat, twice — which hardly rated her as a regular at Jake LaMotta’s. She said the first time she was with her madam and I had come over and asked her why she wasn’t drinking and that she said she was over twenty-one but she didn’t have anything to prove it. She looked over twenty-one now. The size of her chest and the amount of makeup she had on, she could have been thirty-one.”

LaMotta was convicted and served six months on a chain gang. The boxing world might have forgiven him these crimes, as it had already forgiven him so many others. But then in 1960 he testified in front of the U.S. Senate’s Kefauver Committee about the influence of organized crime in professional boxing. There he admitted to throwing the fight against Billy Fox on orders from the mob.

It wasn’t exactly news to anyone in the boxing world, but LaMotta’s cooperation was seen by many as overeager. They knew he’d thrown that fight. Everybody knew. But did he have to show up and admit it like that? Did he have to make the sport look so bad, so publicly?

Writing in The New York Times, Arthur Daley cast aspersions on the whole sport following LaMotta’s testimony:

“Boxing is the slum area of sports, and the forces of evil have thus far been able to prevent any attempts at clearance or rehabilitation. It is ruled by the gangsters’ code of silence. Evidence at a municipal or state level has been too elusive. Perhaps Congress can sweep clear the debris and order the garbage jettisoned. LaMotta’s whistle-blowing is a start, and strange doings of recent years in some of the lighter weight divisions may yet be laid bare.”

After this point, LaMotta lamented, boxing truly turned its back on him. When all the other old middleweights were invited to events to honor Robinson or some other aging ex-champ, he was the only one left off the list. He liked to joke that he had become “LaMotta non grata.”

Feb. 18, 1985: Sugar Ray Robinson (1921 – 1989) and Jake LaMotta (1922 – 2017) joke as they are separated by a guest during Robinson’s birthday party at the Carlyle Hotel, New York.

(William E. Sauro via Getty Images)

When Robert De Niro bought the rights to his memoir so he could play the fighter in Scorsese’s film, LaMotta was working as a bouncer in a New York strip club. In “Sporting Blood: Tales from the Dark Side of Boxing,” Carlos Acevedo portrays this version of LaMotta as relatively upbeat.

“I been a bouncer here for almost two years. I accept it, I don’t feel sorry for myself. Don’t forget I been in jail, in a chain gang, was put in a box in a hole in the ground. And I been punched silly. So this place is not terribly. I do my job. They don’t want me to sit in a window and advertise myself the way Jack Dempsey does in his restaurant down the street. Because here, they ain’t sellin’ me, they’re sellin’ tits.”

Even Robinson, as great as he’d been, wasn’t exempt from the cliches of the fight game. He retired and came back. He spent all his money. He fought well into his forties, turning in sad efforts that only served to remind his fans that all beauty eventually fades. After losing a decision to 27-year-old Joey Archer — a fight in which Robinson was knocked down, despite Archer’s well-known lack of punching power (he had just eight knockouts in 45 career wins) — he finally retired for good in 1965, at the age of 44.

Sportswriter Pete Hamill, who covered Robinson’s final fight from ringside, later described seeing jazz legend Miles Davis approach Robinson in his dressing room after the fight to tell him, as a friend might deliver difficult but necessary news, that he was done fighting.

“I guess I am,” Robinson replied.

He was later diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. Hamill recalled seeing him at a fight in Las Vegas, and being not particularly surprised by then that Robinson didn’t remember him.

“There was no reason he should have remembered me, but he didn’t remember Jake LaMotta,” Hamill said, laughing at the cruel absurdity of it. As if, no matter what else might be happening inside the man’s brain, LaMotta should have been the one memory that would never fade.

“He had a smile on his face, blissed out,” Hamill continued. “But gone.”

Author’s note: A great debt is owed to the following texts, all of which are highly recommended for readers who wish to know more about this chapter of boxing history:

“Raging Bull: My Story” by Jake LaMotta with Joseph Carter and Peter Savage

“Sweet Thunder: The Life and Times of Sugar Ray Robinson” by Wil Haygood

“Boxing and the Mob: The Notorious History of the Sweet Science” by Jeffrey Sussman

“Sporting Blood: Tales from the Dark Side of Boxing” by Carlos Acevedo

“Pound For Pound: A Biography of Sugar Ray Robinson” by Herb Boyd

“Knockout! The Sexy, Violent, Extraordinary Life of Vikki LaMotta” by Vikki LaMotta and Thomas Hauser

Read the full article here