After knocking out Anthony Joshua in the fifth round of a fight at Wembley Stadium last September, Daniel Dubois knew the hard part was still to come, so he could not afford to relax. All around him, in a ring once empty, were people, cameras and microphones, each a reminder his next task was to describe what he had just done. Think boy on the naughty step. Think suspect in the interrogation room. (Think, Daniel, think.) He had found the punches — crucially, a short right hand — but would now have to find words, typically more elusive. Now he would be asked how he did it. Now he would be asked how he felt.

To pass the test, Dubois required words and emotions, two things prohibited during the fight. For some fighters, these things come back quickly, overwhelmingly so, whereas for others, like Dubois, the wait tends to be a long one. He is, when wearing gloves, unthinking and unfeeling, and it can be no other way. It is how he likes and prefers it. It is how he has been programmed.

Advertisement

Chances are, despite the danger of being alone in the ring with Joshua, he felt safe there, comfortable. There was only the referee to interrupt them and only Joshua’s hands capable of either hurting or embarrassing him. He was, to some extent, in control of both the situation and himself.

Then, when the fight ended, so did Dubois’ control. Now he was back among the living, back among those with whom it was tougher to communicate and feel comfortable. Punches, in that world, no longer counted. They had all been thrown. They could no longer command respect, nor speak on his behalf and express his emotions. He instead had to find words. The right ones.

Oleksandr Usyk and Daniel Dubois rematch Saturday for boxing’s undisputed heavyweight titles.

(Bradley Collyer – PA Images via Getty Images)

“Erm, I’ve only got a few things to say, man,” said Dubois, to the surprise of nobody. He then smiled and addressed the 90,000 fans in the stadium: “Are you not entertained?!” Even louder: “ARE YOU NOT ENTERTAINED?!”

Advertisement

As familiar to the crowd as they were to Dubois, those four words may have started with Maximus Decimus Meridius, but had more recently been uttered by Tyson Fury and others in the aftermath of prizefights. For that reason, the words stuck with Dubois and he turned to them, automatically, when expected to speak, despite having been asked a question pertaining to the fight he had just won. It was, in a sense, no more than mimicry; a childlike mimicry. It required no introspection. It required no thought.

The same, too, could be said of the way Dubois went after Joshua at Wembley that night. For even if there was thought and method behind what Dubois had plotted and executed — and there was — the important thing from his perspective was he remained detached, cold, clear-headed at all times. Such clarity allowed him to shake from his mind the underdog tag and the reputation of his opponent, and it gave him the freedom to then attack Joshua from the outset. It also explained why Joshua, the thinker of the two, suddenly looked so overawed when confronted by a man able to clear his mind in a way Joshua, the former champion, no longer can.

Why that is, one can only speculate, but we know this much: Damage and defeat lead to overthinking, and overthinking will often stifle a fighter’s ability to act on instinct. That certainly seems true of Joshua, whose four professional defeats have all given him pause for thought. His first defeat, against Andy Ruiz in 2019, revealed to him and to the world his fragility, while his next two, both against Usyk, highlighted his technical deficiencies. All three wounded Joshua and left him in a kind of no man’s land, stuck between styles and a stranger to himself. If Ruiz reminded him of the need to be cautious and try to think and box a bit more, Usyk then cruelly reminded him of his limitations as a boxer before asking him: “Who told you to think?”

Advertisement

By the time Joshua suffered his fourth loss, against Dubois, he was a furrowed brow of a man; a knot of scar tissue and mixed signals. The last thing he wanted, in that state of mind, was an expressionless, one-track terminator looking back at him — staring not at him, but through him. Yet that is exactly what he got in the shape of Dubois. He got someone whose ignorance was a weapon and whose simplicity and spotless mind was preferable, in a fight, to a mind bloated by bad memories and associations. He got a man with no nerves and only the slightest hint of a pulse. A man empty, fearless, with whom Joshua could neither hang nor connect.

Whether Joshua himself was an ignorant man trying to be a thinking man, or a thinking man trying to be an ignorant man, he wasn’t up to playing either role. In Dubois, he had lost to an ignorant man, and against Usyk, to whom he lost in 2021 and 2022, he was bested by a thinking man. Both losses, aside from being painful, had indicated how far Joshua was from using either ignorance or wisdom as weapons, and both were reminders that being “normal” — that is, neither simple nor smart — is sometimes the worst thing for a professional fighter.

Against Usyk, for instance, that’s all Joshua was: normal. He was not clever enough to compete on the same level as Usyk technically, nor ignorant enough to risk everything and go for it the way Derek Chisora did, if only for four rounds, against the Ukrainian in 2020. As a result, Joshua suffered the same fate as every other Usyk opponent at either heavyweight or cruiserweight. He was tamed, he was controlled, and he was taken apart, psychologically as much as physically. Afterward, Joshua then grabbed the mic and demonstrated the extent of his confusion with a muddled monologue linguists are still attempting to translate to this day. It was in English, yet it made no sense. Usyk, it appeared, hadn’t just beaten him. He had robbed Joshua of language.

Anthony Joshua gets knocked down in his IBF world heavyweight title bout against Daniel Dubois.

(Bradley Collyer – PA Images via Getty Images)

Usyk, meanwhile, was far more coherent. He simply said, “I am feel,” as is his custom, and flashed that gap-toothed smile of his. He is, like Dubois, a man of few words, at least English ones, but that is fine, for nobody is counting. In fact, far from being stunted by the language barrier, Usyk has found comfort in a catchphrase and other eccentricities, seeming at times like a mime artist content to use his face to convey whatever is on his mind. By doing so, he not only defuses opponents by lulling them into a false sense of security, but he retains an element of mystery, which in turn makes him hard to read. His personality might be that of the court jester, but his actions in the ring are those of a genius — and yes, always hard to read. In the ring, Usyk shows that intelligence is not the ability to put words together in someone else’s language. It is instead a different kind of fluency; a different kind of expression. With a language all of his own, Usyk makes right-left, left-right, and everything you do wrong.

Advertisement

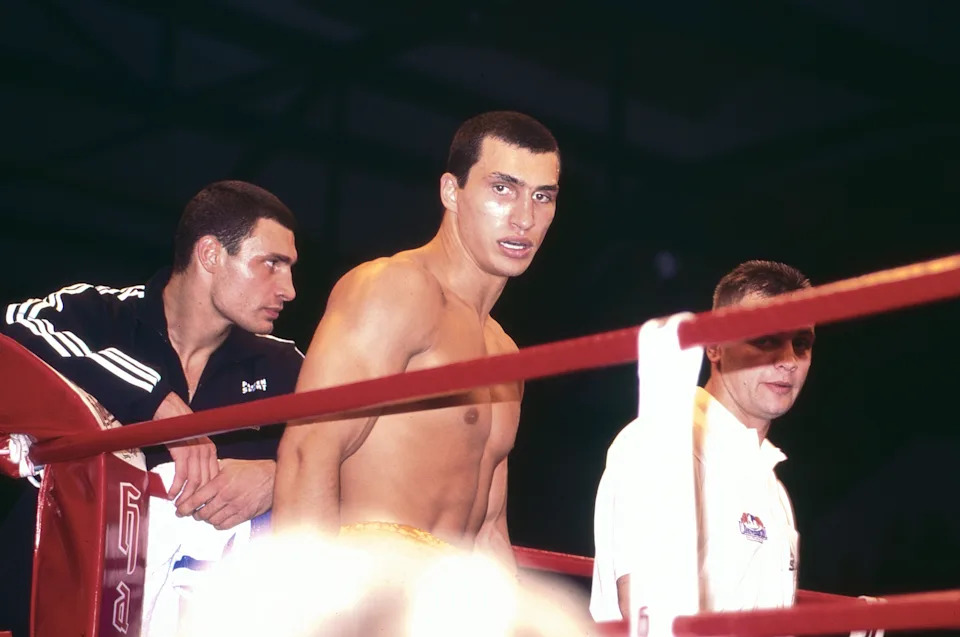

Of course, it’s worth noting Usyk is not the first Ukrainian heavyweight champion whose in-ring intelligence seems out of place in boxing. His predecessors, Vitali and Wladimir Klitschko, were every bit as smart and even had PhDs — both in sport science — to prove it. Vitali, now the mayor of Kyiv, was the older of the two brothers and the one less inclined to smile, whereas Wladimir had the friendlier exterior, a better grasp of English, and a greater interest in America and all it could offer.

On fight night, there were other differences between the pair, and stark ones at that. In fact, often it was said the best heavyweight in the world would be a combination of the two. From Wladimir you would take the left jab and the right cross, and from Vitali you would take the chin and the stamina. You might also look at their minds and combine those as well. For although these were both highly intelligent men, there was a subtle shift in mentality whenever they slipped on boxing gloves and entered the ring. In the case of Wladimir, this sometimes meant a period of overthinking and too much caution for fear of what could go wrong. In the case of Vitali, however, this meant a period of bring-it-on ignorance during which he would become liberated by the permission to hurt and relish the opportunity to give and take punches.

It was quite the switch for Vitali, and one made only more jarring by how reluctant Wladimir was by comparison, especially as his career progressed. One day Wladimir was the intrepid kid queuing up to ride the roller coaster with his big brother, and the next he was the old man standing back, cognizant of both how the roller coaster is made and how it can all go wrong.

The Klitschko brothers in 1999, before their steady march of heavyweight championships.

(United Archives via Getty Images)

Early on, though, it’s true: Wladimir had been as ignorant and oblivious as any heavyweight prospect starting out. He, like them all, fired his right hand with reckless abandon, and he too could see no way that either an opponent could take it or that they would have the temerity to fire back at him. But then, in 1998, Wladimir imploded against Ross Puritty, and with that first loss came a dose of reality and a degree of insight he could have done without. The excavation of self duly began, and everything Wladimir questioned, or doubted, was then compounded when Corrie Sanders and Lamon Brewster added supporting material to Puritty’s initial findings.

Advertisement

For a fighter like Wladimir, an awareness of pain, physical or of defeat, is in itself damaging. After all, an active, high-functioning brain like his tends to struggle to remove memories and associations and has difficulty considering anything, let alone defeat, as “just one of those things.” Moving on, therefore, becomes a little more challenging. It can be done — and Wladimir eventually did it — but often what is required is a complete overhaul, of either style or attitude, and rarely, for better or worse, will the fighter ever be the same.

In terms of Wladimir, some will say he improved for having lost multiple times, but cleverness and caution could never harmoniously coexist and seldom was he given the credit he deserved. His brother, on the other hand, received plenty. He was considered the warrior of the two, if only because he was less cerebral in style than Wladimir and fought with an ignorance easier to understand and enjoy.

Vitali, you see, though beaten twice, had never been beaten like Wladimir. He had lost once by injury stoppage (against Chris Byrd in 2000) and once due to cuts (against Lennox Lewis in 2003), but on neither occasion did Vitali come away doubting himself or internalizing the events and associated trauma. Even if his body was damaged and his face cut up, his mind, in a boxing sense, remained spotless. Good as new.

That ability to not belabor is key to any boxer’s success and has clearly fueled Dubois’ recent form. He, too, is no stranger to defeat, but rather than linger on it, or find himself blunted by it, sallies forth undeterred: head down, keep going. His first loss, against Joe Joyce in 2020, saw the Brit outworked and hurt — he suffered a fractured eye socket — before staying down on one knee to be counted out in Round 10. He was then just as hurt by the reaction to the loss, with many accusing Dubois of “quitting” and suggesting the nature of the defeat was more worrying than the defeat itself. The nature of the defeat, they said, had exposed a certain softness in Dubois, something impossible to remove by lifting weights or hitting bags. But he has, to his credit, since allayed this concern.

Advertisement

His next defeat, in 2023, was inflicted by Usyk, the man he fights this Saturday at Wembley Stadium. In the presence of Usyk, Dubois’ ignorance, so often a tool, was not only magnified but led to him being stopped in Round 9, having had very little success in the previous eight. The only question now, ahead of the pair’s rematch, is how Dubois will react to that second loss and whether he opts to forget it completely or takes from it what he needs. Dwell too much on it and it might cloud an otherwise free and ignorant mind. However, complete ignorance and a disregard for the truth tends to only entice a repeat performance and the same result, with no lessons learned. It is, and always has been, a hard thing to balance and get right. Ask Dubois and perhaps even he won’t know what he plans to do Saturday night. Perhaps that’s a good thing, too. Perhaps that’s the point.

Oleksandr Usyk and Daniel Dubois face off outside Wembley Stadium ahead of Saturday’s undisputed heavyweight championship rematch.

(Richard Pelham via Getty Images)

As for Usyk, expect no more thorough explanation ahead of Fight 2. He also believes in the maxim “show, don’t tell” and has smiles, dance moves and a catchphrase if ever he wants to deflect, or keep them all guessing. He will accept Fight 2 is likely to be different, but how different? That is the question.

Dubois, once a challenger, now has a belt — the IBF title stripped from Usyk — and Usyk, who claims the other belts, is smart enough to acknowledge that his opponent, at age 27, is a different fighter from the one he disciplined two years ago. In a word, Dubois has matured. He is filling out hand-me-down suits and inside them feels grown and powerful. “Tell this little boy he can’t disrespect me,” said Joshua ahead of their fight last year. Yet Dubois, in the end, did more than just disrespect him: He reminded him how it felt to be young, free and fearless.

Advertisement

Now, having come of age, Dubois is encouraged to make himself heard and has both a platform and an audience for whenever he finds his voice. He also has experience, as both a boxer and a man. No longer a boy, and no longer home-schooled by his dad, Dubois has, in his 20s, been busy learning other lessons — some painful, some harsh — and has even been lucky enough to have been schooled by the greatest teacher of them all: Oleksandr Usyk. The problem now, of course, is Dubois must try to use everything he learned from that teacher against him, something only the bravest student would ever attempt. Either that or the most ignorant.

Read the full article here