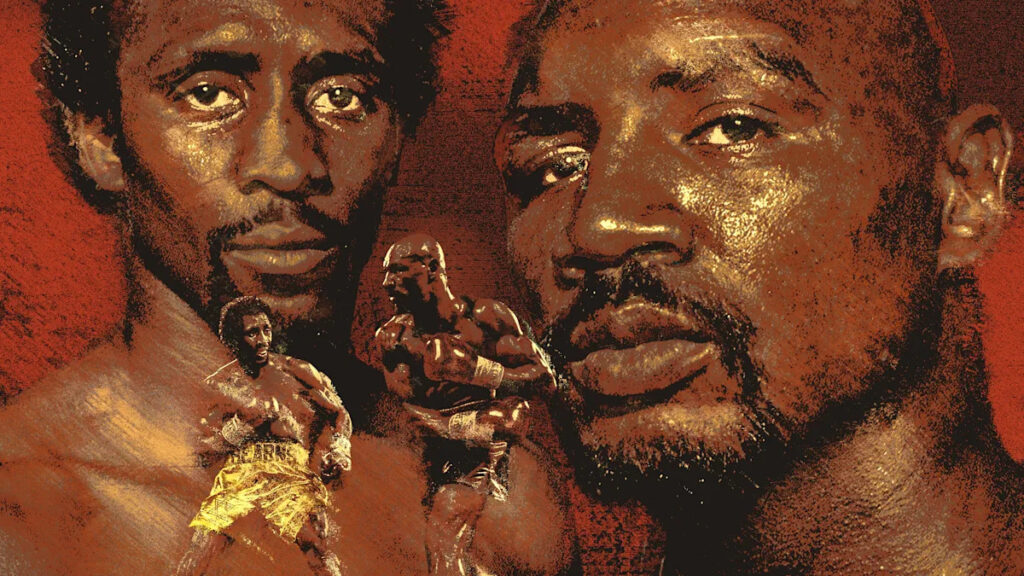

Later it would go down as the greatest eight minutes in boxing history. The first round would be remembered by many as the single greatest round the sport had ever produced. But in the months leading up to that historic night 40 years ago today, there were serious doubts that Marvin Hagler vs. Thomas Hearns would ever take place.

And what a shame that would have been. Hearns, the lanky, mercurial knockout artist who’d gone up in weight and flattened Roberto Duran with one hissing cobra strike of a right hand. Hagler, the hard-headed slugger with a chip on his shoulder, always certain that the boxing establishment was out to cheat him any way it could.

Advertisement

They were practically made for each other. And on April 15, 1985, they made magic together in one furious fight that defined an era. But this was one classic fight that came dangerously close to dying on the vine.

To understand the full story, you have to first understand the strange world of the 1980s. The early and middle part of that decade was, in many ways, a ridiculous time for American culture as a whole. But it was also a tricky time for boxing in particular.

The Muhammad Ali era had ended. The Mike Tyson era had not yet begun. The sport had attractions, for lack of a better word, but it was still starving for real stars. “Sugar” Ray Leonard announced his retirement in 1982 (though would soon change his mind), and there was real concern over whether heirs apparent like Hearns and Hagler could drive fan interest.

In Don Stradley’s excellent book, “The War: Hagler-Hearns and Three Rounds for the Ages,” he describes the ‘80s boxing scene as a bizarre collection of differing characters, all playing separate roles:

“It was a bit like an old Hollywood movie studio, with a leading man (Leonard), a suave, aristocratic type (Alexis Arguello), a brooding gunslinger (Hearns), some matinee idols (Ray Mancini; Sean O’Grady). a crazy stuntman (Aaron Pryor), a dastardly villain (Don King), and plenty of eccentric types, from Frank “The Animal” Fletcher and “Bigfoot” Martin, to Craig “Gator” Bodzianowksi, a stalwart out of Chicago who fought for several years wearing a prosthetic leg.”

Advertisement

Hagler was something of an odd-man-out in that bunch. He had a classic boxing origin story. Following the 1967 riots, his family moved from Newark, New Jersey, to Brockton, Massachusetts — famous as the home of heavyweight boxing champ Rocky Marciano. As a teenager, Hagler got beaten up at a party by a local kid named Dornell Wigfall, who trained at a nearby boxing gym. It was a humiliating experience. Legend has it that the dispute originated over a girl, and Wigfall easily whipped Hagler before stealing his jacket.

Hagler couldn’t accept this. His dignity demanded that he learn to fight. Since Wigfall learned his craft in a boxing gym, so did Hagler. He would go on to beat Wigfall twice in the boxing ring, both times in events at the Brockton High School gym, the second time by knockout.

But while battling his way up the ranks throughout the 1970s, Hagler struggled to gain the acceptance and appreciation of the boxing world. In an HBO “Legendary Nights” feature on the Hagler-Hearns bout, Hagler recalled former heavyweight champ Joe Frazier telling him that he had three strikes against him: “One, you’re southpaw. Two, you’re good. And three, you’re Black.”

Hagler had amassed a string of knockout finishes, but was devastated when his first bid for the middleweight title ended in a draw, allowing then champion Vito Antuofermo to retain the belt. That 1979 fight was Hagler’s first professional bout in Las Vegas, and it would forever remain a sore spot for him. He was convinced that boxing’s power brokers wanted to keep him out of the limelight — and Vegas was the snakepit that made it possible.

Advertisement

Hagler’s response to this was to double down on a knockout-seeking style. He finally won the middleweight title via TKO the following year in London, then finished nine of his next 10 bouts inside the distance leading up to his meeting with Hearns.

Thomas Hearns knocked out Roberto Duran to retain his junior middleweight titles in 1984.

(Richard Mackson via Getty Images)

Hearns had come up as a brooding, dangerous welterweight. At 6-foot-2, he was tall and skinny for the weight class, but with a sharp jab and vicious right hand that cracked like a whip. He’d learned his craft in Emanuel Steward’s Detroit gym, and after making his pro debut with a second-round knockout in 1977, he went 18 straight fights before he ever saw a judges’ scorecard. Few of Hearns’ early fights went more than three rounds, and he won his first welterweight title just three years after his pro debut.

In 1981, Hearns faced Leonard in a welterweight title unification bout billed as “The Showdown.” Leonard broke all previous boxing records (including his own) with a guaranteed purse of slightly above $10 million (equivalent to about $36.7 million in 2025 dollars) for the fight. Hearns had a guaranteed purse of $5.1 million, by far the biggest payday of his career, launching him into a stratosphere of wealth he could hardly have imagined when he first began his pro career just four years earlier.

Advertisement

Hearns was leading on the scorecards with Leonard’s cornerman, Angelo Dundee, famously telling him between rounds: “You’re blowing it, son!” With one eye nearly swollen shut, Leonard rallied and knocked Hearns through the ropes before finally stopping him in Round 14.

Hearns responded by winning his next eight fights, going up in weight to capture the junior middleweight title, which he defended in dramatic fashion with a blistering second-round knockout of Duran in 1984. Duran had been stopped only once at that point, when he dropped the welterweight title to Leonard in 1980. Even Hagler had been unable to put him away. But one clean shot from Hearns’ long right hand dropped him face-first on the canvas, asleep before he even touched the floor.

This helped drive interest in a meeting between two of the world’s best knockout artists, Hagler and Hearns. By this point, Hearns was the more famous of the two and certainly the better paid. Hagler, who’d defended the middleweight title 10 consecutive times over four years, felt increasingly disappointed with his payouts and his prestige.

He struggled even to get broadcasters to use his preferred nickname: “Marvelous” Marvin Hagler. It was as if, in their minds, that kind of glamour didn’t fit with this steely, stubborn, bullet-headed figure they saw in the ring. In 1983, he finally went before a probate court to legally change his name in order to force the issue, which did at least generate him some quick publicity, even if it was also done to spite ABC’s “Wide World of Sports.”

Marvin Hagler fends off Mustafa Hamsho in his final middleweight title defense before his showdown with Thomas Hearns.

(Bettmann via Getty Images)

At first, the prospect of a Hagler-Hearns fight did not seem like a guaranteed financial hit. First, there were contractual issues. Through his association with promoter Bob Arum’s Top Rank, Hagler was an early signee with HBO. But in those days, HBO was far from a powerhouse in either television or sports. In Stradley’s book on the Hagler-Hearns fight, he notes that when Hagler signed with HBO in 1980, it was “still associated with roadside motels and barrooms, the telltale sign announcing ‘Free HBO.’”

Advertisement

As a premium cable service at a time when any cable subscription at all was seen as a luxury, HBO had around 5 million subscribers — out of 78 million American households with a TV. Hagler’s best market was, unsurprisingly, the greater Boston area near where he’d grown up in Brockton. There, according to Stradley, HBO had only 9,000 subscribers — but that number had gone up more than 10% just prior to Hagler’s first HBO fight, indicating that he did have some potential to move the needle in the New England market.

But as he touted a potential Hagler-Hearns fight, Arum didn’t necessarily want to go with HBO. He was more interested in closed-circuit TV, an early version of pay-per-view that was potentially more lucrative. (It was not without issues, however. Just a few weeks before the Hagler-Hearns fight, the very first WrestleMania had aired over closed-circuit, though audiences in some venues paid for a blank screen and nearly rioted as a result.)

Promotional efforts for Hagler vs. Hearns eventually succeeded with help from an aggressive press tour.

(Focus On Sport via Getty Images)

The bigger issue was HBO’s contractual claim to the fight. While the two sides battled it out, and while Arum began to see that general fan interest in the bout wasn’t great enough to guarantee returns that would equal what he’d promised the various stakeholders, the whole event was beginning to look like a financial disaster.

Advertisement

Then, a very lucky (unlucky) break: Hearns hurt his pinky finger. While jogging one morning, Hearns tripped over a loose shoelace. He put his hand out to break his fall and later noticed a sharp pain in the little finger of his all-important right hand. Initially, reports said it was a minor injury. After a judge ruled that HBO had a legitimate contractual claim to the fight, however, ruling out the closed-circuit pay-per-view option, the injury suddenly seemed more dire.

Wouldn’t you know it? The fight had to be postponed. What a shame.

The delay was suspiciously fortuitous for Arum. It gave him more time to generate interest in the fight, and also helped him negotiate a compromise with HBO that would allow a hybrid broadcast model. Viewers in some regions would have to watch at a closed-circuit location. Others could watch with an HBO subscription. Even some non-HBO subscribers could order the fight as a stand-alone event for $15. The pay-per-view model that would come to dominate major boxing bouts over the next few decades was taking shape.

Hagler was incensed by the delay. He told reporters that for the money Hearns stood to make off the bout, he’d cut his pinky off entirely rather than miss the fight. This surliness was said to carry over into his training sessions, with stories of sparring partners getting battered on the regular.

Advertisement

Fellow boxer Buster Drayton, who worked with the Hagler camp at the time, said he tried to warn sparring partners ahead of time: “I’d tell these guys, ‘When you spar with Marvin, it’s like fighting a title fight. You can’t just go in and spar. Marv don’t ease up on you — he comes to work.”

By contrast, rumors out of the Hearns camp were sometimes troubling. Did he really want this fight? Had he grown wealthy and soft? Was he a lamb headed to the slaughter? His longtime trainer Steward often did Hearns’ talking for him in interviews, assuring reporters that he was as lethal as ever, ready to dispatch another victim with his now fully healed right hand.

Advertisement

But when they toured together at various press events to hype the fight, Hagler’s visible determination had an edge of clear malice that Hearns’ seemed to lack. Hagler often wore a red baseball cap emblazoned with just one word: WAR.

The bout was finally set for Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas, the site of Hagler’s earlier disappointment against Antuofermo. He initially balked at the location, but was similarly unenthused when, for a time, Arum had suggested the Pontiac Silverdome outside Hearns’ hometown of Detroit. As fight night neared, betting odds swung back and forth before just barely favoring the champion Hagler. He saw this as insulting, especially against a fighter from a lighter division, but he was also determined not to give Las Vegas another chance to screw him.

Sports Illustrated’s Pat Putnam wrote that Hagler entered the bout with only one goal: “It was a simple strategy, one that could have been designed by Attilla: Keep the swords swinging until there are no more heads to roll, give no quarter, take no prisoners. There would be only one pace, all-out: Only one direction, forward.”

Hearns and his camp had told reporters that his plan was to stay behind his long jab and keep Hagler at a distance for the first few rounds, then sting him with the right once his initial aggression had waned. But once Hagler charged out of his corner for that first round and got straight into Hearns’ face, that strategy became a distant memory.

The pace of that first round was as incredible as it was clearly unsustainable. Hagler, determined to take judges and officials out of the equation, pushed relentlessly forward. Hearns, unable to resist this invitation to a violent dance, met him blow for blow.

Advertisement

According to the official stats tallied by CompuBox — another new invention in the 1980s, here serving in just its third fight — the two fighters landed a combined 106 punches in that furious first round. Hagler did not even attempt a single jab. Hearns did manage to catch Hagler with several solid right hands, but one landed just above the temple, on the hard boulder of Hagler’s skull, sending a sharp pain shooting through Hearns’ fist. His right hand — his most feared weapon — was broken. But Hagler wasn’t going anywhere, and so neither was Hearns.

Back in Hearns’ corner between rounds, Steward was livid. This was not the game plan. He was supposed to stick and move, not stand and bang. As Hearns said later: “I started slugging because I had to. Marvin started running in, and I had to protect myself.”

Over in Hagler’s corner, blood was leaking from a cut that had opened on his forehead late in the round. His trainer, Goody Petronelli, told him not to worry about it and not to change a thing about his approach.

But after another blistering go of it in the second frame, the cut began to seem like a potential problem. In the corner before the third, Petronelli encouraged Hagler not to risk a doctor’s stoppage. He needed to get Hearns, who by now was visibly winded and at times wobbling on his long, thin legs, all the way out of there.

Advertisement

The concern about the cut only heightened when, early in the third round, a Hearns jab split the laceration even wider, sending blood pouring down Hagler’s face. As he had done earlier in the fight, referee Richard Steele paused the action to let ringside physician Dr. Donald Romero examine it. Hagler’s anxiety only increased. Was it happening again? Were they going to stop it on a cut, or simply give Hearns time to rest, and thereby steal what he’d rightfully earned?

According to Putnam’s account, Romero asked Hagler if he could see through the blood.

“No problem,” Hagler replied. “I ain’t missing him, am I?”

Hagler did not throw a single jab in the first round, opting for nothing but power punches.

(Walter Iooss Jr. via Getty Images)

Indeed he wasn’t. But now it was time to make every punch count. After the restart, Hagler attacked the weary Hearns with renewed fury.

Advertisement

After a right hand behind the ear wobbled Hearns, Hagler lunged in with a perfectly timed right hand that came in under a desperate left hook from Hearns. The punch landed flush on the jaw. Hearns’ long body at first leaned into Hagler, like a drunk drooping onto the shoulder of the man on the next barstool. All Hagler had to do was step back and Hearns collapsed to the canvas.

Just to show how very willing the spirit still was, Hearns managed to beat the count by the slimmest of margins. But rising to his feet was all he could manage. As Steele reached out for his gloves, Hearns collapsed into the referee’s arms. The fight was over. Hagler was once again his own judge.

The fight proved to be the viral sensation of its day. Closed-circuit sales had been solid, though not record-breaking. The pay-per-view telecast, according to Stradley, was purchased in about 20% of homes where it was available, which was a new record for live fights and suggested that the pay-per-view concept itself could work.

In the aftermath, though, it was the word of mouth reports that really pushed interest. Hagler and Hearns had done something incredible, people said, a frenzy that had to be seen to be believed. Newspaper and magazine accounts helped stoke the general interest, and HBO sensed opportunity.

Advertisement

“For a figure near $1 million, HBO bought the delayed-tape rights and then, in an unprecedented move, refused to sell the rights to the major networks,” Stradley wrote. “With curious viewers tuning in to see the already legendary fight, ratings for the first HBO airing hit a hefty 15.8, or a twenty-four share of the fourteen million homes wired for HBO.”

HBO pulled out all the stops to promote replays of the fight, taking out full-page ads in newspapers to alert the public of upcoming rebroadcasts. Replays began a week after the bout, with three separate late-night showings on HBO.

But on April 27, HBO showed the fight for the last time. Those who’d been savvy enough to record a rebroadcast with their own VCR — another booming technology in the ‘80s, as anyone whose family owned multiple recordings taped off television can attest — could still watch the fight any time they wanted. But in an era before the internet and YouTube, everyone else had to either buy the official VHS offering from Active Home Video or else wait around for ESPN Classic to be invented.

In this way, it was a sensation truly of its time, coming along at a technological and cultural intersection that proved to be an augur of things to come. As for Hagler and Hearns, whatever animosity they may have felt in the lead-up to the fight dissipated soon after it. They seemed to realize quickly that they were united in boxing lore by this incredible moment they’d created together.

Advertisement

Even in the immediate aftermath, when Hearns visited Hagler in his dressing room, they were already beginning to appreciate the experience they’d shared.

“We made a lot of money, but we gave them a good show,” Hearns told Hagler then, according to Putnam’s account. “Tell you what. You move up and fight the light heavies, and I’ll take care of the middleweights.”

Hagler, who needed just four stitches to close the gaping wound in his forehead, is said to have laughed.

“You move up,” he replied.

Read the full article here